This majority of this post is the transcript of a speech I made last week at GEMS in Salt Lake City. I had planned to upload a video of my speech alongside the text, but my recording from Instagram has unfortunately disappeared into the dang “cloud” with no sign of reappearing! I know that I haven’t given much background on my treatment experience prior to today, so I’ve also taken the opportunity to provide that before diving into the transcript.

Nearly seven years ago, I arrived in St. George, Utah and took a leap into the unknown. I had been struggling with depression and anxiety for years, exacerbated by unyielding gender dysphoria, and had left my parents with no viable option but to intervene by admitting me to long-term, inpatient therapeutic care.

On May 13th, 2013, I began treatment at Second Nature Entrada, a Wilderness Therapy Program that quite frankly saved my life. To this day, I still utilize many of the tools that I learned during my twelve week stay in the Nevada desert. Afterwards, I was admitted to a therapeutic boarding school in Halifax, VA where although I endured immense psychological trauma, I also acquired the tools that instilled in me the courage to live authentically. Carlbrook was the first place that I came out as trans publicly, and although I initially trusted that a group of mental health professionals would affirm and support my identity, I quickly realized that the administration was paralyzed by their willful ignorance about the trans community.

Working within a system propelled by fear rather than compassion, my therapist felt compelled to out me to my parents. Repeatedly, school administrators insisted to my family and friends that my coming out was simply a “ploy for attention” and that it evidenced a “regression into old patterns.” They also asserted that validating my transness would “impede my therapeutic progress” and isolated me from any source of social support for my identity. For the duration of my two year stay, they remained unwilling to adapt their mindset and programming to accommodate the needs of a trans client.

Last week, my journey came full-circle as I returned to Salt Lake City to speak at the Gender Education and Demystification Symposium (GEMS), a four-year-old professional conference founded to address the imperative need to advance transgender inclusivity and affirmation within the teen mental health industry. I spoke to a group of nearly 200 growth-minded mental health professionals, clients, and parents united by a common goal of fostering therapeutic environments that are more accessible for transgender teens struggling with their mental health — people like my adolescent self. I told them about my experiences growing up trans, shared the story of my time in treatment, recounted the immense euphoria that I’ve found through my decision to transition, and provided insights and suggestions for the mental health industry going forward.

As I walked toward my gate at SLC airport on Saturday morning, I paused as I noticed a Jamba Juice kiosk in the distance. At first, I couldn’t remember why this space felt significant. After a brief moment, I remembered — when I left Second Nature in August 2013 to head to Carlbrook, their transport team dropped me off at Salt Lake City airport with plenty of time to spare. On my way to the gate, I stopped at this very same kiosk to grab a smoothie because it reminded me of my family’s frequent excursions to our local Jamba Juice before I’d left home.

As I sat at the gate, I gleefully sipped that delicious fruity puree, eyes filled with fear and wonder as I prepared to leap into the unknown yet again, knowing absolutely nothing of the painful yet profound journey on which I was about to embark. On Saturday, I stopped in front of the kiosk for a minute and took a deep breath. As I breathed out, I reflected on the past seven years of trial and triumph, and wondered about the life-changing experiences these next seven years have in store.

I knew from a very young age that I was transgender.

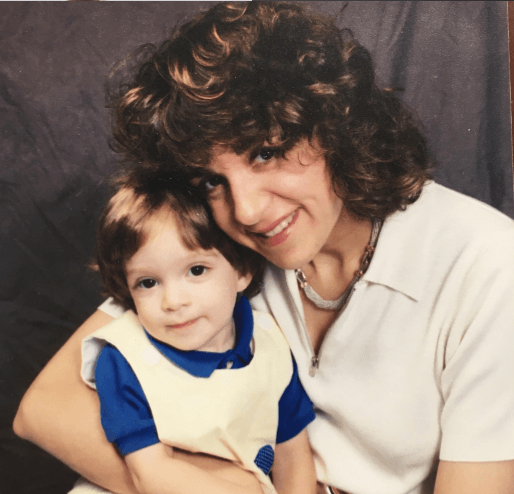

When I was four years old, I looked up into my mother’s eyes and told her, “Mom, I want to be a girl when I grow up, because I want to be a mommy, not a daddy.” My mother dismissed this comment as her “baby boy” being innocent and naive. And she was partially right — I was both innocent and naive. I certainly didn’t know I had the right nor the ability to explore my gender — I had no idea what being a girl meant, no idea how to find my girlhood, no idea that transgender people even existed. I had no clue that the longing I felt was suggestive of an identity that was so often misunderstood and even condemned. All I knew was my deep, unwavering longing to be a girl.

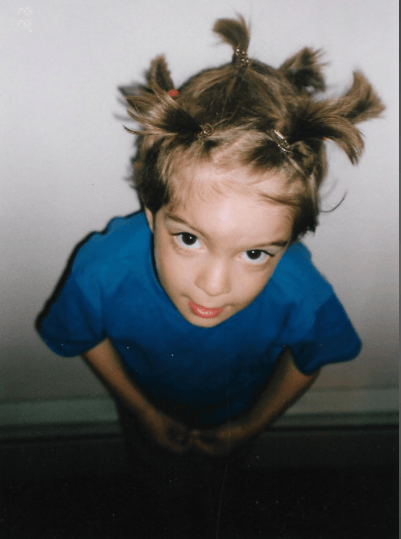

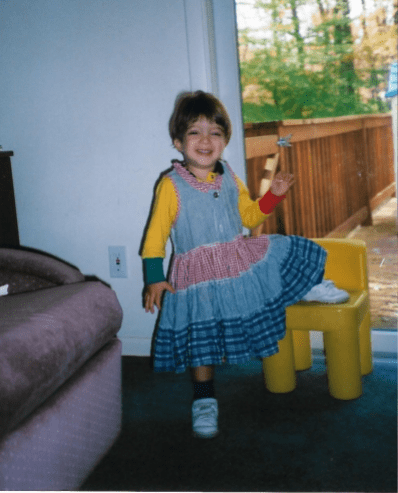

As I grew up, these feelings only intensified as it became increasingly apparent that I was different from those around me. While I wanted to play dress-up, other boys wanted to play sports. While I wanted to sing and dance, other boys wanted to shout and wrestle. While I wore my emotions on my sleeve, other boys had already learned it was probably best to keep theirs inside. For the first few years of school, these differences simply meant that I connected more easily with girls in my class than with boys — but around 7 or 8, play became separate and gendered, and the girls I used to play with at recess and on weekends suddenly wanted nothing to do with me.

I fell to the floor in tears, screaming, ‘I can’t do this anymore, I want to die.’

Now, I have always been an extrovert. Even as a child, I did not do well with solitude, and my social isolation triggered a rapid decline in my mental health. At the age of 8, my mother found me hanging out of our third story window by my fingertips. As she pulled me inside, I fell to the floor in tears, screaming, “I can’t do this anymore, I want to die.”

I didn’t know exactly what needed to change, but I knew I wasn’t happy with my life the way it was. Over the course of the coming months, I continued threatening suicide as my parents struggled to figure out why I was so depressed and what they could do to help me.

it got a whole lot worse.

With the onset of puberty, my struggles intensified. In sixth grade, a bunch of my friends started getting their periods, and I grew acutely aware that no matter what, the differences between us were not going away — on the contrary, they were becoming more stark. I resented these differences, and like many transgender teens, I internalized my resentment as it began to manifest as gender dysphoria, which began to eat me from the inside out. And by redirecting my pain inwards, it became more difficult for others to recognize that I was struggling.

It wasn’t until I was 13 years old that I learned people could be transgender — 13!. My mom and I were sitting on the couch watching Ugly Betty, and they had just introduced a transgender character, Alexis, played by cisgender actress Rebecca Romijn. I asked my mom to explain how it was possible to “become a woman,” as I phrased it then. She explained that some people feel they were born into the wrong body and may have surgery to help them feel better.

Now, although her understanding and explanation of trans identities was admittedly rudimentary at best, the concept struck a chord with me immediately. For the first time, I had a word to describe what I was feeling, and I knew that there were others, too. But almost as quickly as I learned that trans people existed, I also learned how cruelly the world reacted to our existence. This realization pushed me into a state of intense denial about my identity that lasted the next several years.

As I aged further into adolescence, it became painfully obvious that I was not a straight, cisgender boy, but I was so deeply terrified at the thought of being a transgender woman that I tried everything I could to explain away my femininity. In early 2012, my sister helped me come out to my parents for the first of many times, that time as bisexual. My mom expressed her support, and although my dad hugged me and told me he loved me, I could tell he had reservations. He had openly resented my feminine mannerisms and the thought that I might be queer, but I still hoped that he would learn to accept me in time.

Instead, the divide between my father and me grew considerably. He became increasingly uncomfortable whenever he noticed me performing femininity, and once even approached me with tears in the corner of his eyes as he asked me to remove the pink nail polish I had applied just a few hours prior. He started going to therapy to work through his discomfort about having a gay, cisgender child — I couldn’t bear to think of how he’d respond if he knew I was questioning my gender, so I suppressed those uneasy feelings for as long as I possibly could.

I was paralyzed by the implications of being transgender in a world that at that time only referenced us as the punchline of a joke or the victim some terrible crime.

My struggle with mental illness intensified.

My ongoing attempts to deny my trans identity drove me continually deeper into depression — a depression that eventually so depleted my energy and motivation that by the time I was 17, I stopped going to school altogether and spent days on end sitting on my couch, feeling sad, anxious, ashamed, and alone. I was paralyzed by the implications of being transgender in a world that at that time only referenced us as the punchline of a joke or the victim some terrible crime. I had no reason to believe that transgender people could ever be happy, or successful because I had no examples of transgender people who were. By 2012, trans activists like Laverne Cox, Janet Mock, and Indya Moore were not the prominent voices that they are today, and there was very minimal acceptance for trans folx.

I went from practitioner to practitioner, each of them recommending treatments ranging from unhelpful to outright harmful. To be honest, no matter what these folks recommended, nothing seemed to help. For a long time, I blamed myself for my lack of improvement — I thought perhaps if I worked harder at these treatments, that if I became focused and driven and really set my mind to self-improvement, I could find happiness. But the truth is, I could not truly find self-actualization until I confronted my gender head-on and worked through the mental anguish that stemmed from paralyzing gender dysphoria.

By the new year, my public school offered an ultimatum — either I resume going to class and handing in my work, or I find a school better equipped to help me work through my challenges. But after missing the first days back from holiday break, they decided I was too much to handle and my parents were asked to find a new placement. I was distraught. I felt like I had failed, and I continued in a downward spiral. After this, I attended a therapeutic day school for a few months, but as I continued self-harming, threatening suicide, and even began restricting, binging, and purging, my family grew concerned that the support this school provided was still not enough.

It was then my mother reached out to an ed consultant who recommended they employ the help of a specialist to perform a full psychological evaluation. Unbeknownst to me, this specialist diagnosed me with Personality Disorder Not Otherwise Specified and suggested that my parents send me to a wilderness therapy program followed by 12-18 months in a residential treatment center or therapeutic boarding school. He warned them that without long-term, inpatient care, my situation may never improve, and could even get worse as time went on. He did not realize that the “thin young adult with very feminine mannerisms” was a young, closeted transgender girl struggling immensely to come to terms with her gender identity.

My family sent me to inpatient therapeutic treatment.

In any event, my parents hosted an intervention for me where they confronted me with letters they’d written detailing the many ways in which my increasingly erratic, attention-seeking behavior had affected them. Each letter ended with, “Please go to inpatient treatment today.” After they finished, they asked if I agreed to go. The interventionist explained that if I refused, I was no longer welcome to live under my parents’ roof. Scared and sad at the thought of leaving my life behind, I found a friend willing to let me spend the evening, packed a bag, and wheeled it five miles to work.

After one of the most stressful and dynamic weeks of my life — complete with one agonizing night in our local psych ward, numerous tearful goodbyes to my friends, and an impulsive decision to shave my head — I made the decision to go to treatment.

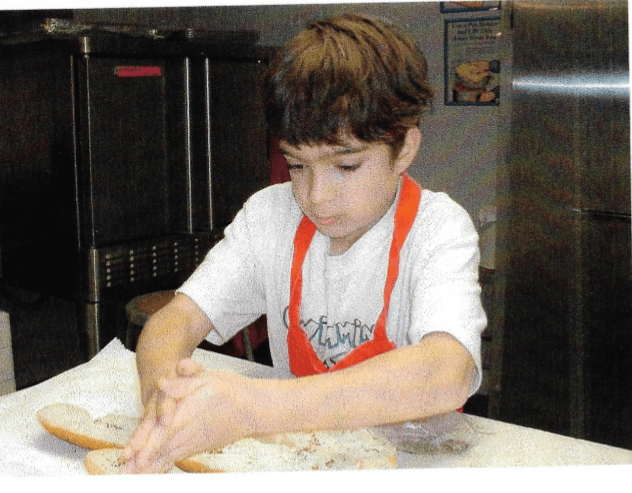

My first placement was Second Nature Entrada in St. George, Utah. To my relief, I was placed in a mixed-gender group, and I was thrilled to learn that my group was mostly made up of women. Away from the comfort of everything I knew — the sheltered suburban town that was home to my family, my friends, my school, and years of memories– the pieces of my life moved in and out of focus as I finally explored lifelong insecurities, fears, and parts of my identity I had long fought to bury.

As I spent more time in treatment, it became increasingly difficult to deny that I was trans. As my facial hair grew and became harder to ignore, so, too, did my gender dysphoria. I would frequently become distracted as I nervously pulled out each hair with my fingers, strand by agonizing strand. I began to consider discussing my gender with my group, but any time I so much as thought about bringing it up, the words felt trapped in my throat as I thought about what finally acknowledging my gender dysphoria might mean for the rest of my life.

i came out as trans… sort of.

But nine weeks into the program, I ultimately decided to discuss it with one of my counselors. I explained that I had been questioning my gender identity for years but still could not fully put my experience into words. In response, they disclosed that they identified as gender non-conforming, and asked how they could support me as I continued to explore my identity.

Meeting somebody else who could relate to my experience gave me the push that I needed to begin to explore who I was and I decided it was time to come out to my group. I had not yet explored my gender enough to put a definitive label on it, but I told them that I had been questioning my gender for years and asked that they call me “Gabby” and refer to me as “she” for at least the rest of the day.

This was my first attempt to lean into the discomfort of gender transition and test the waters of femaleness. To be honest, it was extremely uncomfortable, not because it didn’t feel right, but because I knew that the only reason they were using that name and pronouns was because I had asked them to, not because they actually saw me as female. On that day, being called “she” actually heightened my gender dysphoria because it brought my attention to how trapped I felt within a prison of maleness.

After that, I decided to lay the issue to rest for a bit. At the end of the day, I sat down with the group and told them I still had some things to figure out and to continue using he/him pronouns. My therapist and I discussed my “Gabby” day briefly, but I did not yet have the words nor the resources to truly understand my experiences.

After leaving Second Nature, I enrolled at Carlbrook School in Halifax, VA. Shortly after I got there, I began to tiptoe into conversations about my gender. I started by talking to a few friends, all of whom were supportive. Eventually, I spoke with my therapist, Anthony, who also seemed supportive. Little did I know at the time that Carlbrook was far from a safe space to explore a trans identity.

i came out as trans. again. it did not go well.

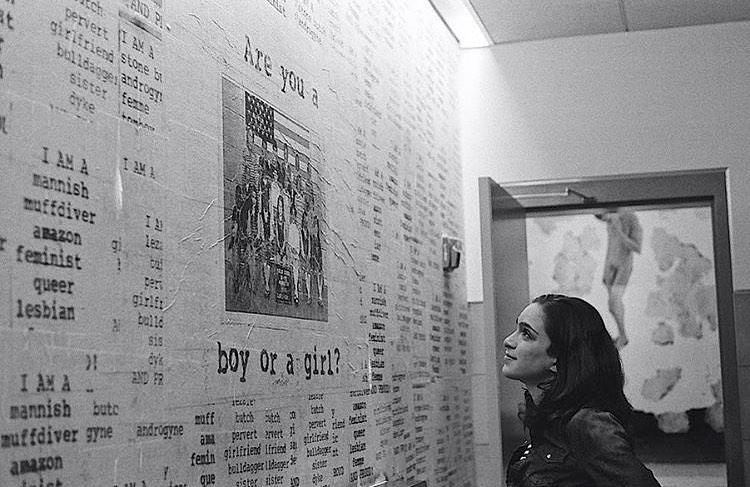

I decided that I wanted to come out to the remainder of my peers and begin transitioning socially, at the very least. On National Coming Out Day of 2013, I asked my therapist to sign off so that I could come out during Last Light, our nightly tradition where students sat in front of the student body and discussed something meaningful to them.

That evening, I sat down in front of 130 of my fellow students and staff and told them that I was transgender, and that I intended to transition while at the school. I also mentioned that I hoped to undergo gender-confirming surgery as soon as I graduated. Now, maybe it was naive of me, but I really trusted that my coming out would be met with love and validation. Many of my peers offered words of support, but looking back on that evening, I should have been suspicious that most of the staff avoided addressing it.

The few days afterwards were pretty calm. A few people asked me questions about my gender, though not nearly as many as I’d expected. I also spent some time reconsidering what my name would be, since “Gabby” had not quite felt right. Through some deliberation, I finally landed on “Arielle” — partially because it started with the same first letter as my assigned name, and partially because it was originally supposed to be my sister’s name, but my grandmother died shortly before she was born and my parents ended up naming my sister after her instead. I did not discuss my Last Light with any of the staff until the following week.

I went up to Anthony one afternoon to ask that he send an all-staff e-mail asking folks to start calling me “Arielle” and using she/her pronouns. He looked apprehensive, and he responded that he thought I was “taking things a little too quickly.” I obviously disagreed, but I was still convinced that I could change his mind.

Assuming I must have misunderstood, I asked what he meant — but quickly realized that he had outed me to my family.

The following Tuesday, Anthony came into the dining hall at dinnertime to walk me to my weekly parent phone call — which was unusual. On the way over, he said, “I have something to discuss with you before your call. I had to tell your parents about your Last Light.” Assuming I must have misunderstood, I asked what he meant — but quickly realized that he had outed me to my family. I was furious — I had explicitly told him that I’d been planning to come out to them when they visited me the next week, though he insisted that he did not remember having this conversation.

As soon as I picked up the phone, my parents confronted me. They were stern and accusatory. They told me that Anthony had told them my coming out felt like a ploy for attention. They saw this as a sign that I was “sliding back into old patterns,” which made them quite upset. Now I will never know exactly what he said to them on their call, but I do know that this is the message they distilled. While I had once been convinced that he was an ally, I realized then that he was not.

I all but refused to talk to him for six months. While I wasn’t quite the activist that I am today, I was rooted enough in the queer community to know that intentionally outing somebody to their family is an egregious violation of trust. I wish he had given me the opportunity to come out myself. I wish he had educated himself on working with transgender clients, and supported me in navigating conversations with my parents — these steps would have been an appropriate course of action.

However, there is an unfortunate discrepancy when it comes to many inpatient programs that primarily serve minors in terms of what information should be shared with parents. Carlbrook had a general rule about what to do when a student was dealing with what they termed a “sensitive issue”: that the therapist discuss the topic with that student’s parents first to help support and coach them to have an affirming first reaction. Now this sounds helpful in theory, but Carlbrook staff lacked the necessary training to coach my parents on how to react to a child coming out as trans.

Over the next few weeks, I came out to numerous teachers and student life staff, and several of them agreed to use my name and pronouns. This went smoothly for about a month, until I noticed that one day, all at once, all of the folks who had previously been naming and gendering me correctly had suddenly stopped. I could not understand why a group of folks who I thought were my allies had seemed to do a 180 overnight, but the change was far too synchronized to be coincidental.

Using a nickname is simply calling someone a different name. What I was asking was that they validate my identity.

Before long, I discovered what had happened. During a staff meeting, a school administrator who had caught wind of my request to these staff members essentially forbade them from using my correct name and pronouns. In doing so, that administrator had isolated me from an extremely important source of support and validation that I had only just discovered. I felt truly defeated, and increasingly scared to advocate for myself within a system that seemed to be working against me from the top down.

Unsure where to turn, I approached the staff member who had told me about their meeting and asked why the administration had made this call. She said that my request to be called by my affirmed name apparently violated the school’s rule against nicknames, which was that all students must use their given name unless their family had a nickname they used for that student. Now, this is a false equivalency — using a nickname is simply calling someone a different name. What I was asking was that they validate my identity.

Around the same time, another administrator held a meeting where he emphasized an expectation he held for the school’s therapists that was most certainly rooted in the administration’s personal fears — “do not indulge anything regarding gender.” They’d only ever had one out trans student prior to me, and I didn’t even know about that person until years later. They clearly didn’t know how to work with me and they were afraid to even try. My very existence threatened the status quo, and if they had chosen to affirm my identity, they would have been forced to rethink many of the gendered expectations and rules that were built into the framework of the school.

At one point towards the end of my stay, the headmaster admitted that they were afraid of how other students’ parents would react if they found out Carlbrook had a transgender student. Through his fear, I doubt he really thought through the implication of that statement, which is that other parents’ opinions on how I lived my life was more important to them than allowing me to pursue authenticity and joy in my own life, and protecting their reputation with those parents was more important to them than protecting their students’ health and well-being.

It was standard at Carlbrook for non-clinicians to allow their fears to overrule sound clinical judgments, and I was no exception. Knowing that they had no training on how to work with transgender clients, the appropriate course of action after I came out would have been to seek information on how to work with our community. This would have enabled them to provide evidence-based treatments. Instead, they discouraged clinicians from seeking external trainings and Continuing Education, and within the geographically isolated, rural environment of Halifax, VA, the administration could easily restrict access to these trainings by denying therapists time off.

Some of the harshest feedback I received was that I was “fake,” but ironically, the same folks giving me that feedback were also denying me the right to be real.

I began to feel my situation was rather bleak. The folks I was supposed to be able to trust the most — mental health professionals who were supposed to be there to support my growth, create a safe environment for me to explore even the most uncomfortable parts of myself, and validate my individuality, were doing the exact opposite. The same folks with whom I had just gone through a two-day therapeutic workshop where they asserted the importance of truth and integrity and spoke at length about the awe-inspiring power of authenticity were fighting against me, not alongside me, as I acknowledged my truth and started along my journey to live an authentic and fulfilling life.

During this workshop, some of the harshest feedback I received was that I was “fake,” but ironically, the same folks giving me that feedback were also denying me the right to be real.

My progress stalled.

This began a period of stunted therapeutic and personal growth as I reached a standstill with the school administration. They continued to insist that I focus on my “other issues” and work on my gender identity after I left Carlbrook, and I continued to try to speak about being trans. Try as I might, I could not convince them that my gender dysphoria was inextricably tied to my other insecurities. Ignoring my dysphoria for the sake of focusing my efforts elsewhere would be like hacking at weeds — you can ignore the roots for a bit, but until you deal with them, the problem will just keep coming back.

The administration’s invalidation of my identity continued to echo out in ripples, slowly infecting every corner of the school. Friends who had initially supported me were told by their therapists that supporting my transition would impede my therapeutic progress. Choosing to trust their advisors over me, several of these friends became frustrated any time I tried to discuss my gender with them, which consequently drove a wedge into many of these relationships.

Any attempt to transgress the gender-based rule system in order to manage my worsening gender dysphoria earned me the label of “troublemaker” and I was made to feel guilty for it. When I tried to grow my hair past the allowed length for “boys” in order to look slightly more feminine, I was coerced into a barber’s stool with the threat of detention until I had no choice but to comply. When I tried to sit with other girls at school assemblies, staff enforced the school’s sex-segregated seating policy, telling me I should “know better” and publicly humiliating me until I complied. When I tried to sit next to two of my female friends on one particular school trip, an ultra-conservative male staff member asked me to move. When I rebutted, “but I’m transgender,” he looked at me and sternly warned, “Do not mess with me.”

Each of my transgressions came with the risk of detention, which may sound pretty innocuous, but being in detention at Carlbrook meant spending ten hours a day isolated in the “detention room,” staring at a wall. For the duration of a detention stay — which could last anywhere from one day to several months — students were forbidden 24 hours a day from speaking or even making eye contact with other students unless their comments were explicitly task-related. Breaking any of these rules resulted in additional detention time. So, naturally, I became terrified of breaking school rules, including the ones that demanded my gender conformity.

Being the stubborn woman I am, I never stopped fighting to make my truth heard. Unfortunately, the administration had the resources to fight back even harder, and their fear of the unknown endlessly clouded their judgment as they stuck by their never-ending excuses for denying my gender exploration. I was denied the right to transition until the day I graduated.

As part of Carlbrook’s grad program, the school required that all students make an appointment to see a therapist before leaving. I was so eager to transition as soon as possible after graduation that it felt imperative I find a therapist who would help me better understand my identity and give me the push I needed to come out and start living as female full-time. I was afraid that if I started seeing a therapist that did not have experience working with people like me, I would find myself reliving the invalidation I was desperately trying to escape. I felt I needed help to find my answers.Though my mother had not fully accepted that I was planning to transition, she genuinely tried to find someone who fit that profile, but was unable.

The first therapist I met with had a beginner-level understanding of trans identity. Though he validated my transness, he unfortunately did not have the knowledge to guide me towards my transition, and I abruptly stopped attending therapy. As I did, I realized that I could not keep waiting for an external source to give me a push — I saw then that the power and strength to transition was inside me all along, and eight months after graduating from Carlbrook, I finally decided to harness it.

Finally, I could be myself — no limitations, no fears, no judgments, no excuses, no need to prove anything to anyone.

I came out again, and this time it stuck!

After twenty years of pain, uncertainty, and the perpetual fear that I would never know the joy of feeling at home in my own body, my whole world suddenly snapped into focus in one cathartic moment of stunning clarity. On August 31, 2015, I stepped onto Ramapo College campus for my very first day as a student, put on a full face of makeup, and in a moment of immeasurable euphoria, exploded into my new life as an out, proud transgender woman. Finally, I could wear makeup without anybody questioning it. Finally, I could ask others to call me Arielle and “she” without anybody telling me no. Finally, I could be myself — no limitations, no fears, no judgments, no excuses, no need to prove anything to anyone. Just me — Arielle Rebekah Gordon — in the euphoric pursuit of my truth.

Though my transition has certainly brought its fair share of obstacles, I can say without a doubt that choosing to live authentically has brought me such profound happiness that it has been beyond worth any pain and frustration I’ve faced. Though it took some time, my parents are now wonderfully supportive allies and have stuck by my side as I’ve navigated my transition.

In the years since graduation, several of Carlbrook’s staff members have admitted to me that when I came out, the administration felt like they were out of their depth in knowing how to support and work with a transgender client. That much is understandable given the state of trans awareness at the time, but what is inexcusable and egregiously irresponsible was their response. Instead of searching for external resources and pursuing new knowledge, as is the expectation in any medical field, they essentially decided that treating a transgender student was not within their protocol so the best course of action was to ignore the problem and hope that it went away.

While Carlbrook blatantly invalidated my gender identity, many of the lessons the program taught me were what eventually gave me the strength to transition. They taught me the importance of courage, truth, and authenticity. They taught me that the key to feeling alive is to follow my dreams and trust myself. And finally, they taught me the power of resilience — the idea that I don’t have to be defined by the pain I’ve endured, but instead can choose to learn and grow from it and define my future on my own terms. That is exactly what I did when I came out as transgender.

Around the eight month mark of my social transition, I began to consider whether or not I wanted to transition medically. As I did, I learned that the state of New Jersey required that a therapist diagnose me with gender dysphoria before prescribing hormones, so I once again began the search for gender-affirming therapists.

I reached out to Laura Jacobs, a trans-affirming practitioner near my home, for an intake. I quickly found out that not only was she trans-affirming, she was actually transgender herself. A few sessions in, she mentioned something called the WPATH Standards of Care, which at that point I had never heard of. According to their website, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health seeks to promote evidence-based care, education, research, advocacy, public policy, and respect in transgender health. Their standards set the industry precedent for affirming, evidence-based practices to treat trans and gender non-conforming people.

What if I wasn’t actually transgender? What if I really was just doing it for attention? Was I distracting myself from my “actual issues” by focusing on my transition?

In our early sessions together, I still carried around the weight of Carlbrook’s invalidation. Though I was out as transgender, much of what the school had told me reverberated in my mind — what if I wasn’t actually transgender? What if I really was just doing it for attention? Was I distracting myself from my “actual issues” by focusing on my transition? After years of hearing mental health professionals — people I should have been able to trust! — echoing the assertion that my identity was simply a cry for attention, part of me had started to fear that they were right. Though I knew my fears were irrational, it took many sessions with Laura before I truly internalized her validation.

I have learned a lot from working with her. She taught me that transgender people deserve to feel validated, trusted, and respected. Through my sessions with her as well as my personal explorations, I have achieved a degree of gender euphoria that I had never thought possible. It is crucial that the rest of the mental health industry adapt to incorporate trans-affirming practices into therapeutic approaches so that future students at therapeutic boarding schools have a more affirming experience than I did. I have several key suggestions for how to do this.

Number one — When somebody tells you that they are transgender, believe them. Give them room to explore their gender, taking their lead and supporting them while they do.

Absolutely no harm can come from validating someone when they come out as transgender and allowing them to explore themselves freely. As a society, we need to normalize gender exploration as a part of life — similar to any other self-exploration, the purpose of gender exploration is to find out who you are. It should not be required that someone knows without a doubt that they are transgender — in fact, that kind of defeats the point! If someone explores their gender and realizes that they’re cisgender, great! If someone explores their gender and finds out they’re trans or non-binary, also great!

Apart from surgery, every transitional step that someone takes is at least partially if not fully reversible, so even if someone who comes out as trans does later realize that they are not transgender, there’s no harm done. What can be harmful is when folks react negatively to someone coming out — reactions like accusing them of lying, not trusting their authenticity, or denying their right to transition.

Although there are certainly instances in treatment in which the therapist does know better how to approach a particular situation, gender exploration is not one of them. Take each patient’s lead as they explore their gender in sessions with you. Allow them to tell you what they need or use evidence-based guidelines to help them find out. Every transgender person is different, meaning that our journeys and the steps required to quiet our dysphoria are also different. Some of us want to take hormones, some of us do not. Some of us want to have gender-confirming surgeries, some of us do not. Some of us want to come out to our families, some of us do not or cannot. And each of those steps is up to us.

Number two — transition-related care is medically necessary to treat gender dysphoria.

Preventing a transgender person from transitioning or delaying their medical transition is strongly linked to autocastration, depression, increased gender dysphoria, and suicidality. Conversely, supporting a transgender person’s transition is strongly linked to an increase in overall happiness, health, and well-being.

When I got out of Carlbrook and started to transition, I noticed something — many of the insecurities as well as the maladaptive coping mechanisms that I had developed to mask them began to fade away. The more confident and comfortable I felt in my body, the less dysphoric I felt, and the happier I was. Now, I won’t pretend that I didn’t have other issues to deal with when I got to treatment — I was anxious, depressed, attention-seeking, neurotic, and scared to be myself. I will however assert, as is the case with many transgender people, addressing my gender identity concerns and allowing me to transition was the key to unlocking my happiness.

Number three — When a child transitions, it is extremely beneficial when their family adapts to support them. You can help facilitate that growth.

As a therapist in an institutional setting where you are working with a transgender child after they have come out to their parents, you have a responsibility to help guide their parents along the journey with them. Take each patient’s lead in this, because different transgender people may ask for a different level of support in navigating these interactions.

As I’m sure we all know, some parents will be much less willing to accept that a child is transgender than others, but most parents will have some level of difficulty accepting it at first. There is so much you can do to help them along their journeys. You can provide them with educational resources. You can share stories of transgender greatness. You can affirm their personal journeys, while providing an understanding that being transgender is not a choice and for folks who wish to transition, transitioning is medically necessary to treat their gender dysphoria.

Transgender children do better when they have the support of their families, and you can play a pivotal role in making sure that their parents know best how to support them.

Number four — Be willing to adjust to accommodate transgender clients.

Affirming transgender and nonbinary clients’ identities challenges the status quo and may force you to reevaluate gendered expectations and rules, but it is important that programs take the necessary steps to accommodate them.

Transgender clients should have access to the same care and have the same freedom to express their gender that they would outside of your facility. If a trans client wants to begin hormone replacement therapy, help them get a prescription. If a transgender girl wants to start using the female dress code, you should not only allow but encourage her to do so. If a transgender boy wants to live in the boys’ house, you must make the accomodations necessary to make this happen, putting the well-being of your students above the assumed discomfort of parents.

Whenever I make this last assertion, people tend to assert that I “don’t understand” and that “parents pay the bills, so you have to make the parents happy.” To them I say no, I do understand that. But what I also understand is that you have all made a commitment to your clients’ health and well-being, and that affirming someone’s gender in its entirety is crucial to fulfilling that.

Number five — if you don’t have the resources to support a transgender student, find them. If you don’t have the knowledge, pursue it. If you still don’t feel competent treating them, find somebody else who is.

I recognize that there is a gap in education for folks in the medical and mental health industries — it is rare for universities to offer in-depth courses on meeting the needs of LGBTQ+ patients. However, the resources do exist to educate yourself, and it is up to each of you to continue to do so throughout your careers. Coming to this conference is a terrific start and I truly from the bottom of my heart want to thank each of you for taking that step — it’s a start, but it’s not an end.

My hope is that you never stop pursuing new information, that you remain open to new research and developments, and that you challenge yourselves to be more knowledgeable and more skilled mental health professionals each and every day. That is the only way that the industry can achieve transgender inclusivity and affirmation as the norm.

Believe us, support us, and help us grow. That is what the trans community needs from you. Our community is asking for your help. The question is — are you listening?

Are you listening?

Pingback: More Than 1 Million Women in the U.S. have penises. sensational! Now Get Over It. • Trans & Caffeinated

Pingback: Trans Identity Through a Mother's Eyes: Learning to Celebrate my Transgender Daughter • Trans & Caffeinated

Pingback: Welcome BACK to Trans & Caffeinated! • Trans & Caffeinated

Pingback: The Number 1 Most Powerful Tool In Our Transgender Arsenal • Trans & Caffeinated

Pingback: The Nurturing, Inspiring Power of a Trans Community • Trans & Caffeinated

Pingback: A Powerful Gender Renaissance: On Continuing to Explore my Gender, 5 years into Transition • Trans & Caffeinated

Pingback: 4 Months to Bottom Surgery: On gaslighting, Agonizing Self-Doubt, & An Eye-Opening Therapy Session • Trans & Caffeinated