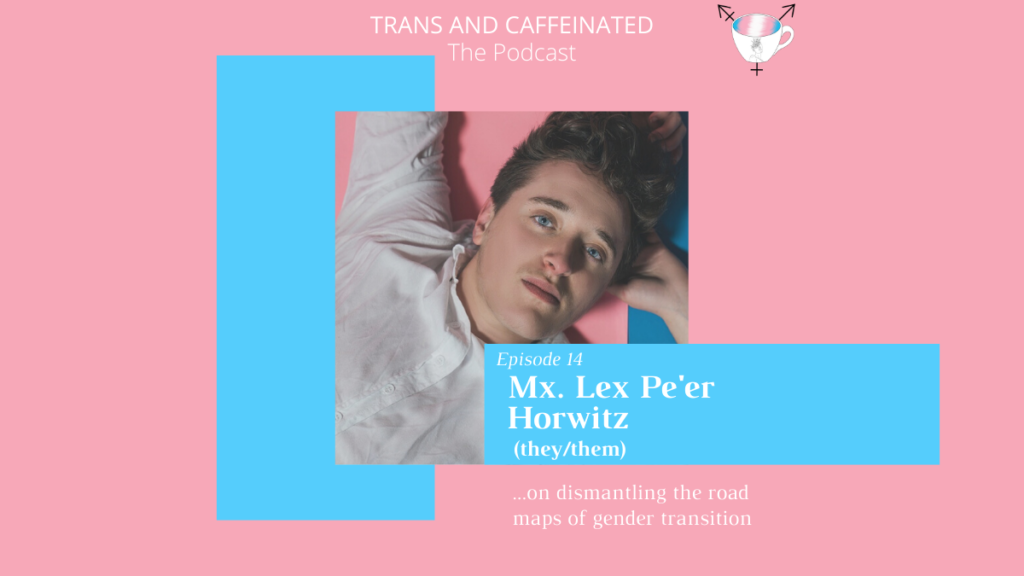

You can listen to Mx. Lex Pe’er Horwitz (they/them) on dismantling the road maps of gender transition, now available on:

Anchor

iTunes (Apple Podcasts)

Spotify

RSS Feed

It will also be available on Google Play, Breaker, Overcast, Pocket Casts, and Radio Public before EOD today (12/13/21). Will update post information when available.

SOCIAL

IG: @lex_horwitz

Twitter: @lex_horwitz

TikTok: @lex_horwitz

Facebook: Mx. Lex Horwitz

Youtube: Mx. Lex Horwitz

Beacons: @lex_horwitz

PAYMENT

Patreon: Mx. Lex Horwitz

Venmo: @lex_horwitz

CashApp: $LexHorwitz

PayPal: MxLexHorwitz

Direct Donations

Beacons: @lex_horwitz

LINKS

TRANSCRIPTION

Arielle: When is the last time you laid down on your bed with a sweet, purring cat curled up on your chest, took a long, deep breath, and remembered to forget the world, if only for a moment? If your answer is “never” or “I can’t remember,” then take a second—if you can—to do that right now. Pause this episode, take a deep breath in, take an even longer breath out, ground yourself in this moment, and remind yourself that it is okay to just be.

This is what Mx. Lex Pe’er Horwitz wants you to remember: that you are enough. That you are okay. That your understanding of yourself and your identity does not have to conform to some pre-scripted road map in order for your experiences and your self-knowledge to be valid.

You are trans enough. You are queer enough. You are right where you need to be.

A jack of many trades—and equally gifted in all of them—Lex shares unique and often profound perspectives about gender and sexuality, transition, mental health, the magic of fur babies, and just life in general. Our conversation was every bit as thought-provoking and transformative as it was hopeful and warm, and you will walk away from this episode having learned something, or multiple somethings, or thinking about parts of the world in a whole new way.

This episode mentions gender dysphoria, gender-based trauma, transphobia, homophobia, racism, depression, and suicide.

A full transcript of this episode is now available at transandcaffeinated.com/transcripts

This is Mx. Lex Pe’er Horwitz on dismantling the road maps of gender transition

Hi there! I’m here today with Mx. Lex Pe’er Horwitz, who uses they/them pronouns. Among other things, Lex is an LGBTQ+ educator, activist, and model. Lex, why don’t you kick us off by sharing a little bit about yourself?

Lex: Well, thank you so much for having me. I’m so excited to be a part of this conversation with you. And, yeah, so, my name is Lex, and I am a queer, non-binary, trans masculine, Jewish human with big femme energy. I am a passionate animal-lover and cat enthusiast, and I… I am located in Philadelphia. That was just a little bit about me.

Arielle: So, you are joined today by one of your fur babies, Saboo, who was—before we started recording—purring.

Lex: Oh. My gosh. She’s a talker, Miss Saboo. She will let me know when she’s hungry, by either purring loudly or truly talking to me. Any time she gets excited, her little purrs, truly, it’s like vibrating half the room, which is definitely what we were hearing.

Arielle: That’s so cute.

Lex: And Saboo, Miss Lady Tooth, they are both the love of my life.

Arielle: Lady Tooth!

Lex: They are the lights of my soul. I do not know what I would possibly do without my two little children. I honestly spend more time on their healthcare, and their self needs, than I do my own—which is something that we’re working one, because I deserve to care for myself, too.

Arielle: Yes, you do.

Lex: Um, but yeah. My two fur babies are just, like, key and central to my life. And they’re both senior kitties, they’re both special needs, and I’ve been a part of animal welfare and humane education since before I’ve been doing my queer advocacy and education. Truly, like, I understand it as: as soon as I popped out the womb, and I saw a cat, I was like, “I relate, and I will help you.”

Arielle: I love that.

Lex: And I just really loved getting to do animal behavior work, getting to volunteer in shelters, and always saw that the senior animals, the special needs animals, whether that was based off of health issues, or truly just being different than other cats, behaviorally—those animals were more likely to be euthanized, to not be adopted, and to not have a chance of finding their forever home. And so I, from a very young age, since before middle school, made it my life’s mission to get as many senior special needs animals, particularly cats, adopted…and, as soon as I was legally able to adopt, starting adopting senior special needs fur babies who are all in a really important part of my life and my family… many of whom have since passed away because of being senior special needs cats, which has been…

Arielle: Yeah…

Lex: I’m honestly constantly grieving from those losses because they really are my children, but I also would not want them not to be in my life, simply because, of course, with life comes death.

Yeah. And so, I was so happy when little Saboobie was on my lap, purring away a storm. Now she’s just drinking away at some water, and is probably going to find herself a little pushed up part of my couch to sit on.

Arielle: Amazing. I feel like people always say, “Oh, can you hear my cat purring through the phone?” and usually I really can’t, even though I’m sure it’s loud. And I expected to have the same response when Saboo popped up on your lap earlier, and… like, y’all! Saboo is loud.

Lex: She really… like, she can wake me from my sleep. She will let you know what she needs when she needs it.

Arielle: She is a very, very vocal senior special needs cat.

Lex: Oh my gosh, yes. Honestly, she communicates better with humans than with other cats, so… that’s one of her many special aspects of her just being. Also, I don’t know if you can hear, but she’s like hitting away at the litter box in the background, so…she just decided to be a part of this podcast episode.

Arielle: I…well, I’ve joked about this in other episodes, but I’ve been talking for a while now about starting like, a spoof version of this podcast called Pets and Caffeinated, where I just interview trans people about their pets.

Lex: It would really be everything. Everything. I mean, I don’t know what it is, but there is something about trans folks and queer folks, and our fur babies, that is just, like, unmatched. That would be everything for the world.

Arielle: Cause they just don’t…they don’t care. Like, especially, especially like, earlier in folks’ transition, like, when…that period of time where it’s really hard to…I mean, it’s often hard to feel understood and feel seen by others, but especially in that really early period of time, where we ourselves are, like, struggling to see ourselves as who we are and struggling to, like, figure out how to navigate the world as a trans person, and then when we have these little fur babies who just, literally, they don’t even register anything about us, they just see us genuinely for their loving humans or big cats, which is what I’ve heard they think we are.

Lex: Truly. And that is such a… that is such a beautiful way of understanding it, too, is just that…the love that we get from our fur babes is not conditional love.

Arielle: at all.

Lex: Like, it’s just unconditional love. It isn’t dependent on our identities, or who we love, our how we choose to present ourselves. It’s truly just based on, “I love you, because we support each other.” I wish all love was like that.

Arielle: It’s so wholesome. And they sometimes also know when I’m having a rough day, like, we have a cat named Puppy, and she…

Lex: Incredible.

Arielle: Yeah, it’s because I call everything cute, “puppy…” It’s a problem. Well, not really, I guess, because now I… now we have a cat named Puppy, so it’s worked itself out.

Lex: I love how that also just messes with, “yes, a cat named Puppy. These words we defined and decided for ourselves, and we can use them in whichever ways we want.”

Arielle: Yeah, right! I wanna get a dog named Pony after I come back from my surgery, I just think it’ll be perfect.

Lex: Please do!

Arielle: It is very much in part of my plan for after I come back to Chicago after bottom surgery, to get a dog named Pony.

Lex: I hope it’s also a small dog.

Arielle: That is also part of the plan.

Lex: Yes, messing with all the concepts! And also, so excited for you and your upcoming gender affirming surgery. That is beyond incredible.

Arielle: Thank you. Yeah, I’m… I’m so excited. People that have followed me on Instagram have seen me go through a very long process in deciding whether or not I wanted it, and I’ve ultimately come to a place of peace with the decision, which feels really, really major in my life. It’s exciting.

Lex: Yeah! Oh my gosh, it’s so exciting. Also, cause I know we both… we share so many parts of our identity.

Arielle: We do.

Lex: Which is incredible, I love to find other queer trans Jews, yes! And the fact that we both identify with some aspect, or form or non-binary identity.

Arielle: Yeah.

Lex: And both also decided that, for our own respective reasons, that some form of medicalization was what we needed, would make us feel the most authentic and the most affirmed in our own bodies. And I think that that’s commonly a narrative that isn’t told or is almost erased or hidden, because of this belief that there is a, quote, “roadmap to transition” or “being trans enough” or if you’re a trans man, then it looks like “X, Y, to Z,” or if you’re a trans woman, following this linear path.

And the truth is that regardless of if you’re binary trans, or non-binary trans, that medicalization, the legal aspect, the social changes, are truly just tools available for us to use, and we don’t have to use all of them. But we have the option to use them all, so I just… this idea that non-binary people either don’t medicalize their bodies because they aren’t “binary enough” or they aren’t “trans enough” is beyond me, and I’m constantly working to dismantle that.

And so, when I meet other non-binary folks and get to talk with them about their journeys to understand what they truly just needed for them to kind of take out that societal pressure of, “these are the boxes that we told you you had to fit in,” but then to really just do the self work to say, “Does that actually work for me? Does that really fit?”

And to be like, “you know what? The opposite of that thing you’re telling me makes sense!” or “you know, this is aligning for me!,” and that’s totally fine, too! So just, mazel. Mazel mazel.

Arielle: Thank you. Yeah, that to me is one of the trickiest parts of navigating trans existence, is all of these expectations that folks have on us based on their limited understanding of what it means to be a trans person… which is, like, you know, people that are trans feminine automatically want bottom surgery, and automatically want to have, like, bigger boobs, and all of these expectations of what people expect from someone based on the fact that they’re trans i really difficult to navigate, cause it makes it difficult to know what is just a societal expectation that we have internalized, and what is actually something that we want.

Lex: Oh my gosh, I totally relate and agree to all of that. And that’s the thing I’m actually noticing lately, that I had believed this misconception that I had either already done the work, or I didn’t even have the work that needed to be done to address internalized homophobia, and internalized transphobia.

And, using those big words, I was like, “well, those aren’t beliefs that I hold, so obviously that’s not something within my being.” But then, realizing that, “Hey, we grew up in a very gendered space, and a very explicitly cis het environment where those were the ways in which you are validated.” And which parts of what I was told were truths are actually things I want for myself? Or have I just said it, and been forced into it so many times that I believe it as a truth?

And so, I just relate so, so fully to that.

Arielle: Yeah, and I kind of want to circle back to what you said about our identity overlap that we share, cause we did discuss the fact that we are both jewish, queer, trans folks who are also non-binary. This is an overlap that I’ve found in a lot of folks, which is unique, uh, I was in an internship in college where three out of the five people in the room were queer trans Russian Jews.

Lex: What an incredible environment!

Arielle: What an incredible environment, right!

Lex: I just… everything about that. I’m fascinated, I want to learn everything.

Arielle: It was… it was a lot of fun. And I’d love to hear about how this intersection of identity affected your experience as a trans person, whether or not religion played a really significant role in your experience, I’d just love to hear what it was like to, you know, navigate the intersection, what it’s like today.

Lex: Yeah. Absolutely. For me, my Jewish identity has been one of the longest identities that I’ve claimed, and that I’ve lived with and lived through and has just been a root part of who I am… and for much longer than my queer and trans identities, which came when I was able to acknowledge those, I have this belief that, when we come out, that’s an external process, but folks so heavily relate on coming out as an external process to others, versus the coming to, the internal process of understanding one’s identities and accepting and loving them.

And, for me, those aspects of my queer and trans identities came later in my life. I’m 23 years old, and it was when I was around 19, 20, that I was finally able to have the environment and the language to understand my queerness and my transness.

And way before that, I was immersed in my Jewish community, in my family being raised Jewish—those aspects of my identity, my Jewish aspects of identity, were a part of me for longer than my queer and trans aspects of identity. And so, understanding how identities are constantly being formed, new parts of our existences are being celebrated.

And I grew up going to synagogue every single week, multiple times a week. My sister and I went to Hebrew school every single… I believe it was Wednesday evening. We’d go to services every Saturday. My sister and I shared our B’nai Mitzvah together, so we had that really important “coming to your adulthood in your Jewish community”—we shared that together.

And the oddest part for me is that I was always gendered as a woman, I was always understood as feminine in those spaces. And there wasn’t the space for me to exist otherwise, and I also didn’t have the language to know that being queer or being trans were actual valid identities… were identities that people held and they are still a very active member of society.

Whereas, in the spaces that—and this is getting into a whole other story of the fact that I went to a, quote, “all girls school” for 14 years. And so, when I talk about being raised, and being immersed in very gendered communities, what I’m thinking of is that—I’m gonna stop saying “quote all girls school,” but that is exactly what I mean every single time, because obviously not all of us were girls, and it’s also gonna get annoying to hear me say “quote” every time, so we’re gonna say “all girls,” but we’re gonna give it a little stare down, we’re a little angry, we’re pissed, it’s not really that.

Arielle: If you’re listening to this, I expect you to make that little stare down every time that Lex says “all girls school,” just to, like, sort of, like, mimic, umm, what Lex would be doing if we had time to put quotes on every…on every usage of that term

Lex: And I will be doing that exact bodily motion every time I say it, too, and it’s gonna give me the wrinkles and it’s fine.

But yeah, just like, being immersed in such a gendered space, and then also, I’ve been doing a lot of self-reflection about my time in Hebrew school, and in services, and being a part of the Jewish community that I was raised in, and how that was also an extremely gendered place. And I’m still working through those feelings, and understanding how all the environments that I was a part of have resulted in who I am today, and my path in discovering my identities.

And the truth is that my synagogue was always a safe environment, it was always a family environment. My Rabbi at my synagogue grew up in northeast Philly with my dad and his two sisters. He was friends with my eldest aunt, and so, it just always felt like an indistinguishable part of who I was was connected to my religion… because, not only was it an active, physical environment that my family and I were always a part of, or constantly engaging in, but also just having such deep roots to our Rabbi, and to our cantor, and the fact that my mom actually converted to Judaism. So, my mom was not raised Jewish, she was raised Christian, and she—when she met my father, and knew that they wanted to spend the rest of their lives together—she converted to Judaism, but before they got married so they could have a traditional Jewish wedding.

And my sister and I were then raised solely in the Jewish community as a religious community. And just thinking about all the different ways that these identities and these communities all come together to really create who I am, and constantly navigate what those processes were like, is forever a very fascinating self-work project that I have going on.

And actually, another thing about being not only queer and trans and Jewish, but talking about my name. My name—my deadname—was based off of both one of my grandparents’ names, and a biblical name, and I was simply just uncomfortable with my deadname. It was an extremely feminine name. I’m just so upset, it would just impact me so negatively when I would hear someone use my deadname, and that happened to be a rationalization for them to use feminine pronouns, or she/her pronouns, or to use gendered feminine language like “woman” or “girl” when that simply wasn’t my experience.

And so, I did end up feeling a lot of discomfort and a significant distance from my birth name— my deadname, but I also knew that when it came time to legally change my name, which is something that I did, that I wanted to keep my connection to Judaism, which was informed by my parents’ names that they chose for me.

And so, when I was choosing my middle name, it was really important that I chose a Hebrew middle name. And so, “Pe’er” is a Hebrew name, and it’s… when I was doing my research, I wanted a name that wasn’t explicitly masculine or wasn’t explicitly feminine. I wanted it to be a neutral name that was just beautiful, and still matched what I wanted. My middle name before began with a “P,” and I wanted my middle name—when I legally changed my name—to also begin with a “P,” but to hold a meaning that I was able to choose, which is an experience that so many people do not have. And I do believe that, as trans folks, we are given this, one could say “unique,” experience—not saying that it’s an ideal experience to have the pressure of choosing your own name, if that is something that one chooses to do, or maybe not even chooses to do, but you’re put in a place that you’re like, “this name doesn’t work for me, so I guess, like, I have to choose a different name.”

And so, I choose “Pe’er,” and the meaning of “Pe’er” is “luxury, magnificence, gloriousness, and splendor.” And it supposedly, based off of the analysis within the bible, it should be used for folks who—and I am reading this from the website that I chose my name from—”represents people who are peacemakers, sensitive, love to please, they hate arguments, tend to mediate complex and sensitive situations, diplomats with high intuition, need love, warmth, and touch.”

And I was like, “a lot of those things are truly who I am. This is the name.”

Arielle: I love that. I love how much thought went into that, and I… that part you said about, you know, as trans people we have the opportunity, or sometimes the discomfort, of having to choose our own name… which gives us a lot of agency that a lot of other people don’t have over what we’re called. And I, for a lot of reasons, liked my birth name, but it was also highly gendered and I got to sit down with my mom and a baby naming book and pick out my middle name together, and pick one that I felt like really captured who I was, not who, you know, two people in a room who had just had a baby thought I… would capture who I was when I was born. Yeah, I think that’s really rad.

Lex: Yeah. Yes. And I Iove the word that you use—agency. Because we are given this agency, and it is unique in the sense that, unless my mom reminded me, “well, technically when folks get married, they may choose to change their name” and I was like “okay, that is true.” However, most times, those folks, to my knowledge, are not going to be changing their first and their middle name…

Arielle: Yeah.

Lex: …which is a different process, because so much of our identities—and I totally, I am not trying to come down on my mom because she is totally right, I was like, “trans people are forced to do this thing that no other people do!” and my mom was like “well, actually! This legal process is really crappy, and I know because I went through it to take your father’s last name.”

And I was like “okay.” So, as with many things, the gendered concepts, or the sexuality concepts that are harmful to trans and queer folks are also typically harmful for cisgender folks as well, which is why the conversation on queer topics is just so important. And it has that overlap with, “okay, well taking someone’s last name is still different than, and related to, well if you’re changing your first and middle name.”

And I Iove that you were able to sit down with your mom and choose that middle name. And that, actually, something really important to me was having my, both my parents and my sister’s feedback on my middle name, because I… I felt very overwhelmed.

Arielle: Yeah.

Lex: I was like, “well, I’m given this opportunity, this agency to choose my name, but I also didn’t ask for this.”

Arielle: Yeah.

Lex: Yeah. And I… I’m not gonna play “should” and also that stuff, because that is a whole other realm of digging your own grave, and I’m trying to get out of it… but this idea that, “okay, I know that a gender-neutral name makes the most sense, and I don’t have a gender neutral name. My parents were not in the slightest informed, or given the language or the environment to understand that gendered names and gendered language could have “X, Y, Z’ impact on your child if they are not cisgender.

And so, it was this mix of “oh my gosh, I’m in this place where I get to choose my name” that also is beyond overwhelming, because I never thought, I was never told as a child that I was going to be trans, that I was going to be queer, and that a part of this identity formation for me was that, “hey, I actually am really uncomfortable with my feminine name.,” and that that’s a process that I have the agency to be able to change.

And my name, being such an integral part of my identity and who I am, being able to have that input, and that support from my family when I was choosing my name, was so important to me. So I love to hear that you also found it really important to have your mom involved.

Arielle: Yeah, it was a really unique experience. I want to talk more with you about this concept of identity formation, and this distinction that you make between “coming to” and “coming out.” On a small tangent, like, one of my favorite parts about doing this podcast is when other trans, gender nonconforming, non-binary folks, like, use a phrase or say something in a certain way that is just, like, slightly if not totally, fundamentally different from the way that I had forever been thinking about a certain topic. And this distinction that you made was one of those moments for me when I was reading it.

Lex: Yes!

Arielle: Yeah, so I’d love to hear what that distinction means to you—both personally, and why it’s also an important, more general reframing of a common narrative about identity.

Lex: Yeah. Oh my gosh, absolutely. I have been working through this phrase for about, like, a year now, and trying to dismantle all these “road maps,” per se. Like, what we were talking about before, like, this idea that, if you’re trans and you’re trans masculine, this is your road map… or if you’re trans, and you’re trans feminine, then this is what you do.

And, in a very similar sense, I feel like we’re told that, when we come out, here are the steps to coming out. Here are…these are the people you tell first, this is the language you use to say it, this is what you should expect, and here are the other things you need to know.

And, just like the sense of choosing our names being different, when we come to our identities or come out, that process, that publicized, that external process of, “hey, this is who I am” is typically what we traditionally think of when folks say “coming out.” We’re like, well, “oh, did you come out to your family?” or “what was it like for you to come out?” This heavily-focused area of, “how did you tell other people who you were?” not “how did you know who you were, and come to love and accept and cherish that aspect of you?”

I really feel like the coming out narrative not only is so predetermined, so based in, “what was the reaction?” vs. “oh, are you supported in the ways that you deserve?”

Or, “what was your trauma? Were you loved and accepted?” And the fact that that’s even a question is, I mean, it’s a very real question, but it’s so disheartening because that means that love is not unconditional if someone can choose to love you based on how you come out to them or the identities that you share with them.

And so, I’ve been doing a lot of self-work and community work, trying to dismantle this idea of like, “why is it so important that we share our coming out story?” And I truly do think it’s important that we share our journeys to discovering our identities, but I don’t think that that is the same thing as what we traditionally think of as the “coming out.”

And so, for me, I’ve found… an easy way for me to understand it is to separate the coming out process as an internal process, which I call “coming to” one’s identity, and then the external process, the sharing with others outside of your being—that being the “coming out” process. Because, for me, I really do understand them to be two completely different processes… when I know, for myself, when I was coming to my identities, that was something that was occurring throughout my entire life, whether I consciously was aware of it or not. Whereas, when I was coming out to people—although, I did technically come out to my mom without, I was not, I did not plan, I did not believe that it was going to happen, that is a whole other very interesting story to share—but, for the most part, I feel like the narrative of coming out can happen, or most folks claim that it happens, in a very planned way. And I guess I just proved that was wrong to myself, because I really didn’t plan my coming out to my mom, whereas I planned it with a couple other of my family members.

And so, even just differentiating, like, “hey, this process, this external process of sharing your authentic self most likely happens after you have your internal process of understanding who you are and being able to share that in one capacity or another with the world.”

Arielle: And you mention, too, that you were in an all girls school, and also Hebrew school, which was a highly gendered environment. And I’m curious to hear what kind of impact being in that type of environment had on your coming to portion of your identity formation process?

Lex: That is something that I am still trying to piece together some memories, just experiences, and really just think about what I was taught, and where it came from. I know that I had my first genderqueer, gender transcendent memories as a very young child, and that I brought that authentic part of myself into all of the gendered spaces I was in. And although I don’t have, necessarily, explicit memories of being invalidated, being shut down, being told that that is not true—I do have some—I can imagine that, in these highly gendered spaces, that is exactly what I experienced, and why I did repress my identities, why I wasn’t able to open up those internal boxes until I was in different environments.

And so, for me, I love sharing my different examples of coming to, because I really do think that—separately from the external process of coming out—coming to one’s identity can also be given a little subtitle, subheading, give it a little A/B process going on here, where you have… some of this is happening consciously, where you’re like, “oh my gosh, am I queer? What does that mean for me?” or “Am I trans? What does that look like?”

And the other parts can be very subconscious, or can be so anxiety-provoking or scary or unfamiliar that you repress those things, and so they do become unconscious until you have to have those memories, those ideas, those aspects of your self-work resurfaced. And so, I had a lot of my gender-transcendent memories resurface as I was exploring first with my gender expression, before I was able to really understand that—”no, this doesn’t make sense that… I’m not a masculine woman, something about that ‘woman’ term. I’m a masculine what? Masculine not woman, masculine genderqueer person.” And so, that was the external words that I was sharing with folks.

But the processes that I was remembering was when I was in Pre-K, I was at a playdate with a friend from Hebrew school, and at that playdate, we had a pair of scissors, and I believe she suggested we give ourself a little hair salon, make-believe playdate, and I was on board. We did a little trim—mmm nothing more than a little bit of an inch. My sister was super happy with her haircut, she looked fabulous. And I was like—and you know, my… let me actually preface this by saying: my sister and I looked like twins, we are technically Irish twins, we’re less than a year apart—and both of us had our hair down to our waist for our entire lives. I didn’t cut my hair to the short cut that it is now until I was in college.

And so, we’re at this playdate. My sister got an inch cut off, and she was really happy with it. And I said, “chop it all off.” And my friend did exactly that, she cut off all of my hair for me, and I could not have been happier. But I was not able to understand this experience of identifying long hair with femininity, and folks wrongly assuming that I was a girl because I lived in this feminine box.

I, as a three-and-a-half-year-old, four-year-old, had those unconscious connections to gender and what was being taught to me, and said, “you know what, that doesn’t fit. Chop it all off.”

Or, my first year at this all girls’ school I just remember—I walked in one day, couldn’t really tell ya what exactly changed within me, but I just told my best friend at the time and said, “Hey. Carolyn. I’m a boy, and my name is Lex.” She said, “Great, Lex. Let’s keep reading.” Like, that was literally just it. I said “I’m a boy, this is my name”—and she said “great, what’s next?”

And so, I have so many experiences where I explicitly identified as anything but a girl, and yet was in such gendered environments that I was told that that was not possible, I was told that that isn’t who I am, and I needed to fit within these boundaries. And I even remember, within the same age range—maybe even a little bit younger—my dad was dressing my sister and I to go and play outside, and he put my shorts on, and I ran out the door without a shirt, and he was like, “Lex, come back! We’re not done getting changed.” and I said “boys don’t wear shirts” and I ran away from him.

And so—I didn’t know who to communicate, like, “hey, I don’t know where y’all got this idea that I am going to be this thing that my sister is, and she seems happy, but that just really isn’t what’s gonna work for me.” And so, the ways that my little Lex was able to articulate, able to say, “hey, this isn’t me, was by identifying purposefully with things outside of the gendered box of “girl” or “woman.”

Or, even if it wasn’t explicitly “women,” the fact that our society misconflates “women” with “femininity” as a standard and ideal, I did so much work throughout my elementary school life to distance myself from femininity. I even, at very, very, strong points in my elementary school, told my friends that I was allergic to nail polish as a way to stop getting nail polish as a birthday present, cause it was something that I either immediately regifted, or had no interest in and gave to my sister. I even said that, because I was allergic to nailpolish, I said that I would throw up any time I saw the color pink—or, it may have been reverse, because I saw pink a lot more and I couldn’t fake that nearly as much as I could fake being allergic to nailpolish.

But I explicitly was finding ways to say, “you know what? Society is saying, like, ‘girls are feminine, and this nailpolish thing, and this color pink is supposedly feminine.’ I am going to distance myself from these things. I am allergic to nailpolish, and I will vomit if I see pink. That is my way of communicating to the world–I can’t possibly be a girl if I don’t like the things that all the girls like.” And it was just something that was consistently invalidated and corrected, wrongly, of course, corrected me back into the box of, “you’re at an all-girls school. All of you are female, all of you are girls. All of you are feminine.” And, “all of you are gonna be straight, or else your lives are going to be hell.”

So, I kept trying to advocate for myself… to share what my actual experiences were with my teachers, with my classmates, and I don’t really remember a specific point where I just stopped, because it got to be too damaging, it got to be too invalidating, where I wonder if I ever just told myself, “Maybe life will just be easier if you do what they tell you to do.” And… I’m crying right now, because that is just so deeply upsetting that that is an experience that so many trans folks experience—”Well, can we be our authentic selves, or will it just be easier just to live someone else’s life but in our body? We no longer have control over what those experiences look like.”

And I can only imagine that, when I was in elementary school, I had to make that decision for myself. I mean, so much of the reason why I talk so openly about who I am, and my identities, and why I’m in the education realm, is to make a world, to work towards this change where this isn’t going to be what all trans childrens’ experiences are… where we can be in a world where we can openly communicate our experiences, and rather than invalidate, and erase, and shut them down, and discriminate, or stigmatize, we openly have the language, and the environments, and the communities to be able to host affirming conversations, and be able to truly support folks where they are. That’s another really difficult thing was that I… I know that my family loves and supports me as my flamboyant, flaming, queer self. And the fact that I was in such a gendered environment at my all-girls school, and that my Hebrew school environment was just inherently gendered because not only is the Hebrew language gendered as masculine/feminine, without—unless something has changed, and I am unaware, having a neutral pronoun or a neutral way of existing—those spaces were just gendered in those ways.

And my parents—they didn’t have the language. They didn’t know that non-binary people, or genderqueer folks, or this idea that, “of course you see masculine women, or feminine men.” But they also grew up in very much so differently gendered histories, and environments, as baby boomers, having very different ideas about what a family looks like, or what a person’s role in a family is.

And I am not saying that my family upholds that, because we absolutely do not. We dismantle the shit out of that stuff. In our household—”hell, no!” But that’s also stuff that I talk with my parents about, cause it’s stuff that they actively are also dismantling in their own heads. “Oh, this idea that ‘X, Y, and Z’ is the case because of these gendered existences…”—we’re going through that work together. And so, there’s a part of me that’s like, “uhh, mom, dad, look at all of these memories that I have of me communicating—whether or not directly to you, or to my first grade teacher, or to my second grade best friend, or to my Pre-K best friend who cut off all my hair—that, ‘hey, something is different here.”

Like, where was the language? Where was the conversation? Like, why wasn’t I supported in that? And having to remind myself that it’s not that they chose to silence and to invalidate me, but it’s that they didn’t have the language to understand what I was going through, as two cisgender, heterosexual people. They were unprepared to have a gender diverse, flaming queer child. Not that they were unprepared to love me, because they love me to the depths of their souls, but to be able to even know how that support begins, where that affirmation starts, and how to validate versus invalidate in those experiences…that was something that we had to experience together.

And so, that’s also something that I’m constantly reminding myself that—hey, we’re doing the education work so we can help parents, we can help guardians, we can help siblings, we can help grandparents, we can help anyone under the sun who is willing to listen to what we have to say, to provide those educational materials to talk about how we use language, and the impacts it has on affirming or dehumanizing, and how that, of course, will lead to mental health disparities within communities that are experiencing such profound forms of invalidation since the beginning of our existences.

Arielle: Yeah. So, I want to talk about your role as an LGBTQ+ educator, and also the way that you tie your mental health and self-care advocacy into that. So, can you kind of share just a little bit, like a synopsis of the kind of work you do around those issues, in terms of education?

Lex: Yeah. So, my education work is primarily focused on educating both queer folks and allies, and, like I said, anyone who has the interest—which I hope would be everyone—in learning about identities that they don’t necessarily share, or even learning more about identities that they may have. And so, for me, it’s providing free educational resources, such as lectures, workshops, facilitations, different PDF and word documents of “this is gender-affirming language” or “here are trans healthcare clinics that will affirm you throughout the United States.”

For me, my education work is really focused on getting as many resources on a range of topics that impact the LGBTQ+ community, and people—primarily trans folks.

And for my advocacy within mental health awareness: for me, that looks like me openly talking about my mental health, and what I do to take care of myself… and to talk about the just stark differences in mental health experiences within the LGBTQ+ community, and compared to straight and cis folks. So, for me, it’s really important that when I do my education facilitations, I not only bring the language and the terms and the experiences into my workshops—but, in order to make it not only relevant, because obviously it’s relevant, whether or not you have the information on mental health—but to show, “hey, when we use these words, you could be saving lives”

Arielle: Yeah.

Lex: “When we affirm people, we are actively helping them to have stability in their lives.” I mean, the truth is that one out of two trans folks will attempt suicide. And… that’s a statistic that many trans, as trans folks we are all too aware of… and even the fact that 97% of transgender people have reported being mistreated or discriminated against at work. Even that 50% of trans folks who have reported having to teach their medical providers about transgender care… so, not only are we experiencing discrimination at work, or in school, but we’re teaching our medical care providers how to appropriately take care of us.

So, of course, all of these things are going to have an impact on our mental health. When we’re in a society that is not only trying to put you into boxes that you may or may not relate to, but you’re put in families that may not have the language, the environment to be able to support you, it makes sense that the experienced homelessness in the trans community for folks that do not have support from their family is 45%. But when you have folks who are supported by their family, it’s down in the 20s.

And I just…I….I…cannot reiterate more how important it is to talk about mental health in the queer community at large, because looking at: comparing the mental health rates to our cisgender or our straight counterparts, there is a statistically significant difference in the rates of poverty, of homelessness, of suicide, of psychological distress, of being able to be involved in a professional world, because how are you supposed to be in a career, when you are fighting for housing, when you are fighting for support and to be recognized as who you are?

So, when I talk, when I do my presentations, I make sure that—”hey, these are the language, these are the terms, these are the things that we need to know, and it’s important that you know these things because it is having a real impact on trans lives, on queer lives. And let’s talk about intersectionality, because you know that when you have those folks with intersectional identities, such as being Jewish and trans—if you are raised in a Jewish community where gender is upheld, you’re likely experiencing a lot of stigma, a lot of potential trauma from multiple realms of your life… not only from your Jewish identity, but from…also from, “is it possible to be trans, because I’m Jewish?” or…

I mean, when we look at, when we look at Trans Day of Remembrance, and we… each year becomes the “deadliest year yet.” I mean, look at who is experiencing this violence, this violence is so heavily impacting, mainly, trans femmes of color. Trans women who share a racial identity that is also marginalized. And so, if we don’t look at the intersections of our identities, then we know that—hey, as a trans woman, not only is this person experiencing potential transphobia, and lack of safety, or homlessness, poverty, whatever it may be because of her trans identity, but because she’s also Black, or Latino, or has a mixed racial identity, that she’s experiencing racism, and stigma, and discrimination on so many fronts.

I just think it’s beyond important to put my educational information in this cultural and historical realm that we’re living in, because it does have real impact on the people that I’m here to support, and I’m here to love, and I’m here to uplift.

Arielle: Yeah. I think one of the most important things that you know, you said, was that—it’s not just, you know, “alright, we learned to shift our language, we learned to shift the way we talk about things because it’s just like nice and good for trans people.” One of the most important things that cisgender and heterosexual folks need to understand is it’s not just, “we want you to talk about things differently because it’s nice.” We need you to shift the way you understand gender, understand sexuality, because it is truly life of death.

Lex: Exactly.

Arielle: And I think intersectionality, like you said, is often this big miss in these discussions. Even with discussions of TDOR, it’s usually part of the narrative that Black trans femmes are disproportionately affected by this violence because of the way that racism, and misogyny intersect with transphobia… but I think it often kind of stops there, it doesn’t often take as much of a racial justice lens as it needs to. The narrative is often really incomplete, and intersectionality in these discussions is everything.

There’s a quote, it’s by Audre Lorde, and it goes, “there’s no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.”

Lex: Mmm. Yes.

Arielle: And that—I try to keep that so on the forefront of the discussions that I have around this, because it is so true. We can’t just look at the experiences of queer and trans folks through the lens of transphobia and homophobia, because every trans person experiences the world differently based on so many different factors, like experiencing houselessness, like lacking family support, like being within communities that are not affirming… and all of these discussions need to be part of our education because they save lives, because people are out here dying…

Lex: Exactly.

Arielle: …from suicide. Like you said, trans folks are disproportionately affected by suicide. And it’s not because we’re so depressed about being trans, it’s because the world is often overtly hostile towards our identities.

Lex: Yes! That is… brings everything to this idea that, for whatever reason, that also leads to a lack of support of the trans community, that misconception that, “oh, well, it must be something inherent in you as trans people that is leading to that very horrific statistic.” And the truth is that—obviously, we know that that is simply not the case, it has to do with the fact that we are born, and raised in a society that marginalized us, erases us, ignores us, invalidates us, and actively supports violence against us because we are trans.

Arielle: Yeah.

Lex: And so, this made me think of—the DSM used to have being trans as a mental illness. It used to be called Gender Identity Disorder, GID. And finally, in 2012, the American Psychiatric Association took out being trans, right, GID, as a mental health diagnosis, and replaced it…I guess, not even replaced it, but decided that—because it’s more accurate—a diagnosis of gender dysphoria makes more sense. Because it’s not that being trans is a mental illness, it’s that the dysphoria that we experience, or the mental health consequences we experience because of the discrimination, harassment, trauma that comes our way simply because we are trans individuals, causes us that distress.

And so, the fact that the American Psychiatric Association made that shift in, “hey, we were wrong, we were always wrong, right? This is not a mental disorder. But you know what is wrong? The way that society is treating folks that is resulting in this distress.”

Arielle: Yeah

Lex: And commonly, that distress is understood as gender dysphoria. I think that there’s a lot of room to not only understand gender dysphoria as something that, for many folks, is a shared experience of a discomfort with who they are and how the outside world is either expecting or assuming that they are…but I truly cannot even begin to highlight how important this shift was. Because, although they didn’t explicitly say, “hey, it’s important that the reason we’re shifting this diagnosis is because it’s not that trans people have a mental illness, it is actually because the way that we treat trans people is so horrific that we are giving them heightened anxiety, heightened depression. We are forcing them into poverty, into homelessness, into situations where suicide seems and feels like the only option.” It’s not that that is anything inherent in transgender people—that has to do with the fact that it’s a consistent experience because of the place our society is in.

Arielle: Well, this leads back to something that I…I’ve done a lot of unpacking of what gender dysphoria actually is, and the way that I like to understand and frame gender dysphoria is that is a result of years of gender trauma.

So, people love to go on this whole thing of, like, “well, if gender is a social construct, then why is gender dysphoria a thing? And why do trans people exist? And blah blah blah.” And that’s a whole other can of worms that I don’t know if we have time to open right now. Um, but for me, gender dysphoria is rooted in years and years of gender trauma, of years and years of us being told that because, you know, because I am able to grow facial hair, that that is something that makes me masculine, or something that makes me “man” And after years of hearing that, it begins to be something that is not just an external societal thing, like, we internalize it, it turns into internalized transphobia, it turns into gender trauma that we carry with us.

And even if I walk around saying, like, “yes, I know that there are some women with facial hair that are cis women, and I know that facial hair doesn’t make me less of a woman,” years and years of having this narrative reinforced about what makes a man a man, what makes a woman a woman, what are feminine qualities, what are masculine qualities, it sticks with you.

Lex: Absolutely.

Arielle: And it’s really painful.

Lex: It’s so painful. And I know, based on my experiences, one of the ways I’ve understood it is that when I’m in gendered spaces, and I am being forced to understand myself in a gendered way that is just unnatural for me, it almost feels like I have to trade a part of my heart, or part of my soul, in order to simply exist, when that isn’t an experience that cisgender folks shared.

And I really relate to how you understand dysphoria as this process of dismantling years and years of gender-based trauma, and gender-based societal ideals and truths that are impacting our ways of understanding our beauty, and our truths. I know that, for me, it was really difficult for me to finally come to the conclusion that top surgery and testosterone were exactly what I needed, because I knew that—or at least, I believe that—if we were in a world where, just because someone had a chest, or someone had breasts, that they wouldn’t automatically be assumed to be women, that I very well may have been comfortable with a feminine chest.

But, because of our society and the ways that we make assumptions, and we act on those assumptions, and those assumptions can be so harmful, it was too detrimental to my mental health for people to consistently be wrongly identifying me as a woman. And one of the things that I could do to protect myself against that was to have a flat chest, to have a masculine chest, because that is one of the very visual signals in our society that says, “oh—no chest, masculine.” Masculine is associated with “X, Y, Z.”

Arielle: Yeah.

Lex: And so, it was really difficult for me, because I said, “I don’t wanna play into these systems. These systems don’t make sense. These systems aren’t based on anything inherent or natural.” Literally, if our society just accepted the fluidity of identity and experience, I wouldn’t have to get my tits chopped off… I could have tits, and I could decide to bind or expose or do whatever I wanted with them when I felt like it, but I also knew that our society—at least, in my perspective, and I am an optimistic person, this is very pessimistic, so I want to just preface that this is pessimistic, and I do not like it—but that our society simply wasn’t there yet. I would have to experience years upon years, and maybe even a lifetime of people wrongly identifying me as a woman simply because of my body. And that was something I knew, for my mental health, I simply could not go through.

So, for me, knowing that I wanted to have top surgery was the first thing that I knew. I was just very uncomfortable with my chest, and how people had wrongly identified me as a woman because of it. And so, before I even thought about taking testosterone, I knew that top surgery was an absolute need for me.

Arielle: Yeah. Well that connects to this idea of gender-affirming treatments, be they, you know, hormones, or surgeries, as an act of self-care.

Lex: Oh, absolutely.

Arielle: You know, because you are saying, like, this is something that is, for whatever reason, detrimental to my mental health—whether it is an internal thing, or it is that external, like, “society is just not there yet, and I know that, because of this, I’m going to continue to be perceived in a way that I don’t want to.” Sometimes, the biggest act of self care that you can take is by making those, those bodily adjustments in the ways that are affirming to you, for whatever reason.

Lex: Absolutely.

Arielle: And I, I think that process is so unique to every trans person. Like, I’ve gone through this a lot with my bottom surgery process, because I wasn’t sure that I wanted it. And it took me years to really come to a place where I decided that it was something for me… but that’s not something that’s understood by a lot of cis folks, because even cis folks’ understanding of trans folks is still rooted in this gender binary that stems from colonialism.

Lex: Exactly.

Arielle: It’s these Christian ideals of gender and, like, the purity of femininity, and the curves, and the softness, and the tenderness that goes along with femininity, and the caring roles, and all these hypergendered things that go along with femininity and like, being able to bear children, and being, like sexually submissive, and having a vagina, and having breasts, like all these things that are rooted in this binary understanding of what it means to be a certain gender. And it constantly weighs on us.

Lex: Yeah. And how it’s really just so…so entrenched in body politics, in gender policing, in the…the true system of gender and sex was put into place to have women as property, to be able to control marginalized bodies with access to…whether it’s physical property, such as land, or literal human beings which are absolutely not property, and the fact that these ideals, these norms, have made it into modern day history… it is exactly what is happening, and for me, as someone who has done a lot of work to understand that there have always been more than two genders. In the same way, there have always been more than two sexes—and all you have to do is look into the history books, to look into different cultures, and different societies. And to even… if you open up an accurate American history book and learn about the genocide and the policing that were non-white bodies, you understand why our Western culture upholds very rigid, very misogynistic, racist, every honestly negative thing I can think about, in the ideals is simply to be able to control marginalized identities, marginalized bodies, marginalized communities.

And that is simply not something that I am ever going to support. And I’m doing the work every single day to dismantle and to bring the real history to folks, saying, like, “hey, in these cultures, these identities, these concepts are really nothing new. The thing that happened was like, we were lied to, we were told that this is what is best, this is the way it is, and that this is how it’s always been.”

Arielle: Yeah.

Lex: And that is just not the case.

Arielle: Yeah. And I also want to acknowledge, like, the work to dismantle that is really heavy work, it is really emotional labor, and it brings us back again to this point of self-care. And I’m curious to hear what self-care looks like for you, while you are navigating not only being a queer, trans person, but also being a queer and trans educator, dismantling all these ideas and oppressive notions—not just for yourself, but for others—what does self care look like for you?

Lex: Uh, self-care is something I’m actively working on continuing to do, because it is a part of my being that I put other people before myself, I love to take care of others, to support others.

Arielle: Animals, fur babies.

Lex: Oh my gosh, my fur babies, exactly!

Arielle: I circled that at the beginning. I was like, I’m gonna come back to this point that Lex was just, like, I wrote, “called to help others” in quotation marks, and this idea that you’ve always been a caretaker, you’ve always been someone who puts people or other creatures first.

Lex: Yeah, that’s so true, and it really has just… it is just who I am. I don’t necessarily understand it, but it’s also not important that I do, because that is simply who I am as a human on this planet. And so, giving myself to others is my preference. And so, when I’m told, you know, “you should be actually taking care of yourself, too,” and how important it is to actually be able to take care of yourself. It doesn’t even matter what type of work you’re doing… and I mean, like, we’re talking about the, the emotional burden of dismantling all of these very damaging concepts, and a lot of the work that I do is to engage in challenging conversations, to talk with folks who adamantly disagree with me, to try and get open dialogue.

And so, I have decided, I have been putting a more consistent self-care routine into my life, which I highly recommend to folks cause it’s a great way to hold yourself accountable for taking care of yourself.

And so, daily, what that looks like for me having a routine. I’m someone who thrives when I have consistency, when I know what is coming next… the idea of uncertainty is something that has been a catalyst for a lot of my mental health in the past, and in the present. And so, simply having a routine in the morning… knowing that, when I wake up, I get ready, I do the litter boxes, I give my kitties their food, and then I give each of them their respective medications. And then what do I do?

And although that sounds maybe, like, not really like self-care, cause it’s like, you’re just doing your routine. Like, for me, I’m taking care of myself… I’m making sure that my space is clean, I’m making sure that my babies have everything that they need to have a good day.

And then I get to have these moments throughout my day where I spend a certain amount of time with each of my kitties. So, whether that’s having them sit on my chest as a compression blanket, or saying little love coos to them as they’re resting in their beds, or… unfortunately, more often than not, these days, finding little pieces of fecal matter and saying, “let me clean that up for you.”

Arielle: The things we do for our pets.

Lex: Yeah, truly, the things we do for our cats! But oh my gosh, my kitties are certainly a form of my self-care.

Arielle: Yeah.

Lex: Whether that is just being in their space, or getting to pet them, or listen to their purrs. And that’s a daily occurrence that truly is my, the way that I power myself up for the day, get myself ready to do dinner…anything that I need, I’m like, you know what? Am I overwhelmed? I think I need a Lady on my lap. Am I feeling so overwhelmed that I’m having a system overload? I need Saboo to sit on my chest and crush me. Like, I, these are the things that I need and my cats, my fur babies, are there to support me in those ways.

And then, other ways that I do my self-care are…I try to, at least once a week, maybe once every two weeks, paint my nails. And I find that to be a very therapeutic experience, both just the process…

Arielle: Yeah.

Lex: …of painting my nails, and then also the fact that I look fucking fantabulous afterwards. And I’m like, “you know what? It’s doin’, it’s a little boost in the confidence, and it’s just the act of the process itself. Yeah.

Arielle: So does this mean you’ve overcome your allergy to nail polish that you told people you had?

Lex: Oh, yeah. Oh, I overcame that in such a glorious way when… and it was interesting, too, this is such an interesting idea that I really upheld, personally, this concept of masculinity that was very traditional masculine: “Well, I will wear pants, and a button-down shirt, and that means that my hair will be short, and I… my mannerisms are ‘bro.’” Like, really, the thing like, “If I’m gonna have this chest, and I’m not going to have masculine hormones, I have to constantly be performing this masculinity simply to be understood as masculine, then this… I don’t have access to femininity. Pink can’t be my favorite color, because if I say pink, then they’re gonna wrongly assume… going back, honestly, into the same headspace as when I finally came to my queer identities, being so scared of being misidentified or invalidated that I was forced back into a binary box.

But then, as I got my top surgery, as I was on testosterone, and I started to finally live in and as the person that I am in the body that is mine, I realized, “ooh, you are certainly masculine, right? Like, you identify with masculinity, but there is just this… as I will say again, flaming aspect of my identity that I still can’t…I simply…I mean, you don’t even understand how much I’m moving my hands, and my neck, I’m doing a little bit of stretching after how much I’m moving it right now, but just, there’s something about my energy, I’ve decided, is just very feminine.

Or just, maybe not my essence…I’m sure that I’m gonna find other words that will describe my relationship to masculinity and femininity, maybe in clearer and more in the “a-ha” moment kind of ways. But the way that I currently have it is: it’s my energy as a masculine person, who’s also feminine. And so, when I finally was able to realize, now people are not wrongly identifying me as a woman, they’re wrongly identifying me as a gay man. And neither of those are true, because I identify as queer and non-binary. But nonetheless, being misidentified, right, still is not correct, as a man means that folks are visibly understanding my masculinity

Arielle: Yeah.

Lex: Which may or may not have to do with the fact that I had top surgery, that I’m on testosterone, I certainly believe that those are the cases…and also, weirdly, this room…to be my feminine self, to have my mannerisms be what they are, and my voice intonations do their thing, and to hair flip as many times as I want, and to say, “you know what?” with as many hand motions and snaps that need to come when they need to come.

Arielle: Yes-uh!

Lex: And I found that beauty in finally being identified as masculine. Still being misidentified as a man, but that identification as, “oh, you’re a masculine person, and that’s what I’m picking up by assuming what your identities are.” I’m like, “you know what, you got the masculine part right. Amazing. You’re actually now giving me the space to be immersed in my femininity, too!”

And so, I did indeed get over my “being allergic to nailpolish” and throwing up any time I saw the color pink…especially, actually, I’m not sure if you’ve heard, there’s a brand called Trans Guy Supply, and I absolutely love them. They are a trans run and owned small business that is primarily catered to the trans masc community, and they asked me to partner with them to produce a nail polish named after me. That was with the past year, year and a half, and I still was very much so in my masculine self, in feeling constrained, potentially, by, “well, if I start being my feminine self, is society going to continue to misidentify me, but we just did all of these body modifications to have that not happen. So what’s nailpolish going to do to it?”

And I just got to this point where they were like, “we want to name a nail polish after you, and it’s a pink nail polish.” And I was like, “you know what? Great! This is going to be a great way for me to… and we’re gonna get… we’re gonna get both of these gendered experiences, in a positive lens, with a nailpolish that is pink, that is named after me, amazing.”

And so now there’s going to be a pink nail polish called LeX Factor that I use…

Arielle: That’s a great name, too.

Lex: Right? They were like, “you get to name it.” And I was like, “I have a couple of ideas,” and I was like, “LeX Factor,” both because “X Factor” being the factor everybody wants, and that it’s a play on, like, “Mx.,” as I’m “Mx. Horwitz.,” and having that “X” be very emphasized as a gender-free identity.

Uh, and even working to identify colors as–these colors have no gender. They never have, they never will—but what they do have are societally constructed, gendered notions that are telling us that it should be this way. But, we’re really just talking about expression. So, my self-care has actually become an active way that I am working to unteach and dismantle the ways in which I’ve had to, in a very confined way, communicate who I was and what my identities were with people. And I found ways to bring them back into my life in a positive way, which is honestly just so beautiful, because it’s not that common that I’m able to get closure on a lot of experiences that I’m having, and I felt as if this was one of the only instances in my life where I was really able to come full circle.

Arielle: Yeah. It’s really interesting, something my best friend said to me recently, who came out as trans masc not too long ago, was, “Arielle, I just want to be masculine enough so I can feel comfortable being feminine again.”

Lex: Yeah.

Arielle: And I just find that so fascinating. And like, it…it leads back to that idea that you were bring up earlier, of dismantling roadmaps, dismantling gendered expectations of people, dismantling this idea that there’s, like, any one way to experience a trans identity, to experience gender, cause those ideas are just so simply untrue and so limiting. I didn’t transition just so I could be boxed into femininity the same way that I was boxed into masculinity for my entire life. I just… I don’t, I don’t want that. That’s not, that’s not the life that I want for myself.

Lex: Yeah.

Arielle: So, thank you so, so much, Lex, for making the time to chat with me today. Do you have any words of wisdom that you’d like to share before we close out?

Lex: Yes. A couple things I wanna share.

Arielle: Yeah.

Lex: A message that I wanna leave folks with is that there is no right way to exist. There’s no such thing as being “trans enough,” in the same way we were talking about there’s no road map to your non-binary, or to your trans identity. And I just want folks to know that you don’t have to have language, you don’t have to have labels that perfectly align at any point in time, or ever, you don’t ever have to have this language, but it’s here for us if we want to us it, to help us find similar others, to help us find community and affirmation with folks that share those aspects of ourselves.

And this idea that you have to know who you are at a certain point in time, or that someone is too young to understand who they are…just, the hypocritical nature of everything that we are told, you’re either “too young” to know, or you’re too old and you’ve lived this life, why would you, quote, “change”—we’re not “changing”—now? It’s just this work of—you are who you are. You get to use whatever language, whatever terms work for you. And it’s also valid if none work for you, or if you want to just say, “fuck all of that, I don’t like the idea that we socially constructed these terms in the first place, and you’re trying to make me go into these boxes again.”

I just want folks to know that there is no right way to understand yourself, to come to love yourself, to come to then share who you authentically are with the outside world. We’re all on our own journeys, on our own paths, and I strongly believe that this is a journey that I will be on for my entire life. I believe that identity and existence is fluid, that if I work to claim a static identity, I would be limiting myself [from] the most beautiful parts of human existence and being a part of this world.

Honestly, it may be great to be so critically thoughtful about the language and the terms that we’re using to make sure that we don’t put ourselves back into these boxes that we’re actually trying to get out of. And that whoever you are, wherever you are on your journey, you are so valid, you are so worthy, you do have… you have nothing to prove to anyone. You have everything to prove to yourself, in how you love, and support, and cherish yourself. And your journey is yours. And yours only.

Arielle: That was beautiful. Now I’m tearing up. Uh, and where can people go to find you online, or support your work? Where can they access your resources?

Lex: Yeah, so I am on Instagram, Tiktok, and Twitter. @Lex_Horwitz. So, that’s spelled L-E-X underscore H-O-R-W-I-T-Z. I want to reiterate—my name is Horwitz, with a single “o,” cause that is something that is always misspelled. And I am over it, so I am gonna spell it out every time now.

Arielle: Please do.

Lex: But, yeah, so, Instagram, Twitter, Tiktok, I’m also on Facebook. I have a community group called, or community page, called “Mx. Lex Horwitz,” all the same spelling.

And you can also—if you are interested in engaging in a affirming, loving community of like-minded folks, I have a community on Patreon and you can, so, Patreon is spelled P-A-T-R-E-O-N, and you can find me on Patreon at Mx. Lex Horwitz, or you can even search “Mx. Lex Horwitz” and that is a platform that I use to very consciously cultivate a space for supportive and affirming community, it’s where I share behind-the-scenes of different projects I have going on, or a lot, I had a Chanukah unboxing with the kitties, where I took videos and pictures of them opening their chewy presents, and I shared that with that community, and that’s a way for folks to— and I have tiers ranging from $1 to $30, I have like a 1, 3, 5, 10, 15 range—and that’s a way for folks to get, like, behind-the-scenes access, or get to be on my close friends list on Instagram, and just, it’s a way for folks to get… not only get to be a part of my life in more intimate ways, but also for me to be able to share myself in those ways with others while they are providing me the financial stability to be able to create free resources that are available to all, who aren’t able to join my Patreon. So, I use it as a funding way, to be able to continue to produce the work and the educational materials that I do for folks that need access to those materials for free.

And then also, the last thing I will say is that I do have a website, which is LexHorwitz.com, and that’s for folks that are interested in learning more about me, and my advocacy, my mission. I also host a series of urgent-need programs, I also have a list of small, queer, trans-owned shops where we should be putting our money in this capitalist world, because we need to be supporting those in our community in every way, shape, and form that we can. And it’s another way where folks can make donations to my work through my website, and so, I highly recommend checking that out because all of my educational resources are on my website for free.

Arielle: Rad, awesome, thank you so much. And all of that information will also be in the show notes for this episode. So if you missed any of that, you can click the links there. Thank you so much, Lex, for making the time to chat with me today. Do you have anything you want to add?

Lex: The one thing I am gonna say is should I bring Miss Saboo up to see if she’s gonna purr?

Arielle: Oh my god, yes—Pets and Caffeinated, y’all! Pets and Caffeinated!

Lex: Right? That would be everything. Everything. Oh, Saboobie! I’m coming for you. Oh, here we go. Hi, angel. Alright, we gotta get the purrs going. Oh, sweetness, I gotta wake you up. Oh, my god, my baby. I’m gonna give you kisses, hugs, I’m gonna nibble on your ear.

Arielle: This is actually a teaser trailer now for Pets and Caffeinated.

Lex: Truly! And also, I don’t know how to—you know what, of course she’s like, “I’m on camera, so no.” But, at some point in time—it’s okay, sweetness, I know, I just demanded a lot of you and you were not ready. Well, I…sorry. Because she’s not just sitting on my lap. That’s all we’ve got, cause she’s half awake, half asleep, not really sure what is going on. Um, but I will make sure to put content out on my pages of my perfect little fur babes doing their little melodies of purrs.

Arielle: Yes, please. I live for it. Yes.