As a child, I hated being transgender.

I used to dream of being cisgender. I’d close my eyes at night and wish for a spell to strike me in my sleep, praying that I’d wake up and discover I had magically turned into a cis woman. I didn’t even entertain the idea of transitioning because, well, what good would that do? I’d grow breasts and maybe one day, if I could afford it, I’d buy a vagina. But what would it matter? I would never get to have the girlhood I missed, I could never carry a child, I would always have to fight my pesky facial hair from growing back.

At that point in my gender journey, I had come to believe that being assigned male precluded my ability to ever feel whole (no pun intended — okay, okay, pun slightly intended) in my womanhood. Years would pass before I proved to myself and those around me that this was a lie.

carlbrook’s administration still had no idea what to do with a trans student.

After nearly a year of appealing to the Carlbrook administration’s emotions so that they’d permit me to explore my gender, I decided to take a bolder approach. In the months before my graduation, I bluntly asserted that my new therapist, Jessica, allow me to discuss my identity in sessions and tailor therapeutic assignments to my gender exploration. It was a last-ditch effort to fight back in the administration’s endless crusade against my self-discovery, and unsurprisingly, it backfired. Sure, Jessica agreed to give me a journaling assignment. But the topic?

“How do you reconcile with the fact that you will never be a complete man nor a complete woman?”

In the years since my graduation, I’ve learned that a portion of our therapeutic assignments were actually designed by the administrative staff and simply delivered to us by proxy of our therapists. Though I was admittedly angry with Jessica, I now understand that this question was likely an admin’s brainchild.

“What do you mean?” I asked her, taken aback by the inflammatory implications of her question.

Carlbrook’s definition of “complete womanhood” was closely aligned with the exclusionary rhetoric I had desperately hoped I could start to unlearn.

“Well, it’s similar to what we often ask women who find out that they’re barren. It helps us address the feelings of loss triggered by the realization that they can never carry children.”

“I see,” I remarked, realizing that Carlbrook’s definition of “complete womanhood” was closely aligned with the exclusionary rhetoric I had desperately hoped I could start to unlearn.

However, as the diligent and dedicated therapeutic boarding school student I was, I completed this assignment to the best of my ability.

I don’t remember the exact details of my response, and unfortunately (or, fortunately…) my school computer is long gone. If I had to guess, it was probably along the lines of, “I’ll never be a complete man because I’m literally not a man, but I’ll never be a complete woman because I can’t carry babies and also my parents will never accept me as a woman and also I’ll never be pretty and also how could I ever afford bottom surgery and also my lack of a girlhood will always color my perception of the world and also this assignment is honestly just making me feel worse about myself, how on earth is this the best starting point for exploring my trans identity?”

Okay, so I didn’t actually say that last part, but I definitely typed it and deleted it a few times before handing in the assignment. Anyway, real cheery thoughts, you get the idea.

Of course, Jessica’s assignment wasn’t the first time I had heard this sentiment, and it certainly wouldn’t be the last. It echoed nearly every message about trans existence I had received up to that point.

“Oh, ‘he’ wants to be a woman,” strangers and loved ones would comment as an out trans woman flashed across the TV screen. In those few words was a definitive statement on how these folks viewed transgender women. In their eyes, we merely “wanted to be women,” but as I’d later hear so boldly stated in Jessica’s assignment, we would “never be complete as women.”

Though I actively questioned the validity of their logic, I did not have the tools to dispel these exclusionary myths.

Carlbrook held a gender-essentialist ideology.

The controversy at play here is that there are multiple approaches to explaining what makes someone a woman. Carlbrook repeatedly took the oh-so-trans-exclusive bio-essentialist approach, implying that certain biological abilities inherent to many female-assigned people grant them exclusive access to the highest degree of womanhood. In their eyes, this degree of womanhood is fundamentally inaccessible to people without these abilities, which means that being transgender precludes one’s ability to be “complete.”

Furthermore, such gatekeeping of womanhood also reinforces the misogynistic notion that motherhood somehow “completes” a woman’s identity. By maintaining child-bearing as a precursor to completion, this approach asserts that a lack of desire or an inability to have children somehow makes someone “less woman” than others.

These days, I can easily articulate these flaws. Back then, though I actively questioned the validity of their logic, I did not have the tools to dispel these exclusionary myths. I had initially hoped that my time in therapeutic treatment would help me become more comfortable and affirmed in my identity. Instead, it simply compounded my fears.

Would I truly never be a complete woman? Was transitioning even worth the pain and effort, knowing with a newfound certainty that I’d have to settle for a womanhood that fell short of my hopes and dreams? Would I ultimately be just as unhappy as I was prior to transition?

When I began living as a woman full-time, I had yet to answer these questions. I remained painfully afraid that I might never be happy as an out transgender woman. This was a possibility, for sure, but I knew with absolute certainty that I could never be happy living as a man. With this in mind, I took a leap of faith (erm, leap into faith? The Good Place fans? Anyone? Bueller?)

For the first year I was out, I had one goal — to be read as cisgender. Every step I took was with the intention of looking, sounding, and acting in the most stereotypically feminine way possible to prove that Carlbrook was wrong, I could be complete.

By a year into my transition, I had achieved this. By perfecting the art of makeup, training my voice a few pitches higher, buying bras and breast forms, and learning how to tuck, strangers began consistently reading me as a cisgender woman.

Something didn’t feel quite right.

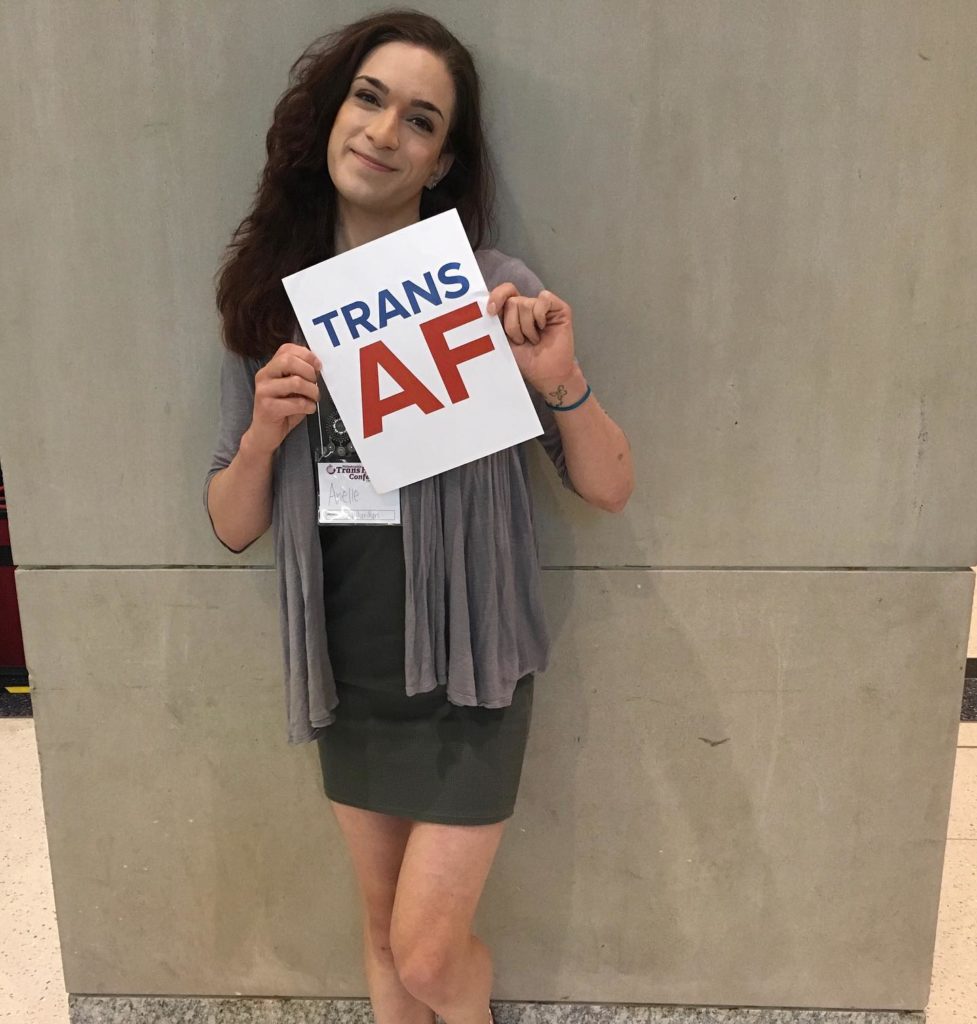

For some reason, something still felt off. It took a while to put my finger on it, but I eventually realized that by allowing others to continue believing I was cisgender, I was also allowing them to erase a part of my identity I had long searched to find and recognize. Furthermore, by neglecting to celebrate my transness as a part of my womanhood, I was awarding power to the narrative that being trans inherently means being incomplete.

This is not to say that every trans person must celebrate their trans identity. Being out as trans can often be terrifying, and it is up to each individual trans person to decide what degree of disclosure is right for them. Not disclosing is valid, selectively disclosing is valid, and asking others to acknowledge your transness without invalidating your gender identity is also valid.

I will never be a cisgender woman, and that’s okay, I don’t need to be. My womanhood is no less valid than any cisgender woman’s just because I’m trans.

An inability to be cisgender does not equate an inability to be complete. For me, the inverse has ultimately proven true; by wholly acknowledging and celebrating my trans identity, I won control over the narrative that others had previously written for me, and in doing so, finally felt complete in my womanhood.

Be transgender! all the cool folx are doing it 😉

I will never be a cisgender woman, and that’s okay. My womanhood is no less valid than any cisgender woman’s just because I’m trans. My lack of a uterus or vagina, my facial hair growth, my Y chromosome – none of these make me any less woman. Some women have penises, and frankly, it’s time that people get over it.

I know who I am — I have always known who I am — and my self-knowledge is more than enough to affirm my identity. I don’t have to “pass” as cisgender in order to prove my validity, and I don’t have to hide my transness just to make it easier for cis folks to accept my womanhood.

I can just be me.

Woman as hell, and trans as fuck.

Pingback: A CLIENT PERSPECTIVE to Fostering a Trans-Inclusive Therapeutic Environment • Trans & Caffeinated

Some women do have penises. Some women do have penises. I agree and we should all get over it. We should all be inclusive of one another.

You’re a trans woman. Trans women have penises. That doesn’t make them any less of a woman. Let us all recite together the mantra, “trans women are women.” It doesn’t matter whether or not you dress in women’s clothing, or anything else about you — you’re just as much of a woman regardless. Good day.