cw: Transphobia, suicide, mental illness

I’ve included a resource guide at the bottom for queer and trans folx who are struggling with mental illness. If you feel you are at risk of suicide, you can call the Trevor Project hotline at (866).488.7386 or dial 911 to be connected with U.S. emergency services.

September is Suicide Prevention Awareness Month, and although this is an incredibly emotionally taxing subject to blog about, I’d be remiss to not use my platform to discuss the overwhelmingly high rate at which transgender people experience mental illness and die by suicide. I’ve touched on my experiences with depression and anxiety in my last two posts, but I want to speak directly to the connection between trans identity and mental illness both for myself specifically and for the greater trans community.

I received my first psychological diagnosis when I was seven or eight years old. At the time, I met diagnostic criteria for Bipolar II Disorder — I went through periods of depression, interrupted occasionally by bouts of hypomania. Though my official diagnosis has changed a number of times, I have consistently experienced depression, anxiety, and occasional suicidal episodes.

As a child, I never quite felt that I fit in with the kids in my class. I was a bit shy, sensitive, unathletic, and could easily have been described as a “teacher’s pet.” Although I couldn’t really explain why, I saw myself as one of the girls from the time I was young. However, it was clear that they didn’t see me this way, especially when social activities became separate and gendered around age 7. Since I had little interest in spending time around boys, I felt increasingly lonely and isolated as my female friends continued to put space between us. On top of that, I was already being bullied for “being a girl” and “being gay” — taunts which evidence an underlying cultural aggression toward both femininity and queerness — but which I was still far too innocent to truly understand. By the middle of second grade, I sank rapidly into my first depressive episode. My mom recalls that my mental health declined in response to the anti-depressant Paxil, but beyond this, I can’t remember exact details of the following months or what happened to intensify my pain.

By June 14th — my sister’s birthday — I reached a critical breaking point. On this day, I climbed out the window of my parents’ third-story bedroom and onto our roof. I began screaming back inside that I was going to jump and moments later, I heard my sister scream downstairs to my mother. I looked down as my mom appeared on the front yard, clearly panicked but quickly and logically taking action to protect her children, as my mother has always done. She was already on the phone with the local police to explain the situation and ask for help. I can’t really describe what was going through my head or how close I was to actually throwing myself over the edge, but what I can tell you is this: I was in immense, overwhelming pain that had so worn me down that at seven years old, I wanted to end my own life. Though I wouldn’t have recognized this so succinctly or clearly at the time, my inner turmoil stemmed largely from incredible discomfort related to my gender and the challenge of trying to form a clear self-concept in a world that expected me to be somebody I never wanted to be.

After this incident, I spent a little under a week in Four Winds psychiatric hospital then returned home to my family. By this point, the school year had concluded and my family and I had the summer to attempt to stabilize my mental health. My mom began searching for a new therapist and psychologist, hoping that I could benefit from a combination of talk therapy and effective use of psychiatric medication. However, as I entered third grade, I continued to struggle. By mid-year, I began refusing to go to school and though my mom tried to fight me on this at first, she eventually realized that it was to no avail. By early 2004, I was unable to function in class and stopped attending school altogether. My mom describes days on end that I would sit in the armchair in our living room, watch hours of television, and be largely unresponsive when anybody tried to talk to me. My mom spent the following months looking for a school with the capacity to provide the emotional support I so desperately needed, and eventually landed on a therapeutic school in Whippany, NJ called Calais. At Calais, I had the support I needed to make it through the school day, but neither I nor my family understood by that point the truth that sat at the root of my depression.

This was the first of several depressive episodes I faced throughout my life. The second notable one hit around the same time as puberty, shortly after I noticed myself becoming extremely jealous that all my female friends had started to get their periods and grow breasts. Around this time, I began to grow increasingly aware that I was a girl while simultaneously sinking deeper into denial about it. Around 12 or 13, I learned for the very first time that trans people existed while watching the Pilot episode of Ugly Betty with my mother. In this episode, the secondary lead’s sister — who he formerly believed to have died in a tragic skiing accident — revealed that she had actually transitioned. I asked my mom to explain how somebody could “become a woman,” and she explained that, “Alexis is transsexual” (a term that was commonly used to describe trans people at the time, but is now considered pejorative and has been replaced colloquially by the term “transgender”). Learning about the existence of transgender people was a catalyst for the long, arduous, and often painful journey of coming to terms with my gender identity.

As I continued to undergo puberty, I found myself overwhelmingly jealous of the changes my female friends were experiencing. I became fixated on the concept of periods — the idea that this experience seemed to unite every woman I knew and the understanding that I would never be a part of that. I felt cheated. The growing disparity between my lived experiences and those of my friends rapidly intensified my dysphoria (though I did not have this word to describe what I was feeling at the time). It was during this time that slumber parties became a major battleground and area of contention between me and my friends, a struggle which I explain more in depth in my first post, You’re “Really Trans” Now! Congrats on the New Vagina!

Between coping with the frustration that puberty brought about, the obstacle that this frustration put in my relationships, dealing with puberty hormones, battling dysphoria, being bullied for reading as queer and femme, and navigating a strained relationship with my father, I sank deeper into my depression. Though I don’t recall threatening suicide during this episode, I consistently contemplated ending my own life. In early adolescence, I most frequently coped with my pain by seeking attention and validation from others, and spending all my time with others in order to distract myself. I poured myself into schoolwork and extra-curricular activities and became obsessed with getting straight A’s, being part of every club, and performing in my school plays because of the way this put me in the spotlight and earned me praise. I wanted more than anything for people to love me because I found myself so unable to love the person I saw when I looked in the mirror. These behaviors are not readily interpreted as signs of a struggling teen, so I was able to skate by without anybody in my life noticing how depressed I was. I don’t really remember pulling out of this episode, and in reflecting on my adolescence, I think that my depression sort of just lingered until early adulthood when I decided to come out as trans.

Toward the middle of sophomore year of high school, my inner Arielle demanded to be heard — though I’d tried for years to deny to myself that I was transgender, my dysphoria began to overwhelm me and I rapidly descended into the deepest, darkest depression of my life. During this time, I became further fixated on the idea of periods and often distraught that I would never get mine. As I slowly began to disclose my trans identity and this fixation to my close friends, I became frustrated as they questioned why I would long for something so unpleasant. For me, the physical pain of menstruation sounded preferable to the emotional pain I was in. Every time that a close friend got her period, it served as a reminder that I would always be different. For the same reason, I became increasingly pained when “being a boy” meant that I was excluded from “girls’ nights” and slumber parties.

It was during this time (age 16) that I came out as a gay male in a desperate attempt to contain the queer inferno blazing inside me and to gain respite from the relentless pressure by my classmates that I come out as queer. In coming out as something that I wasn’t while simultaneously wrestling with a burgeoning transness that I was not yet ready to acknowledge, my mental health took a huge hit. I started self-harming in the summer before junior year — the blood I lost while cutting myself came to symbolically represent the blood that I would never lose due to menstruation. I began using self-harm to “replace” the periods that would never come, cutting more frequently when I knew a close friend had her period in order to approximate the feeling of sameness I so desperately craved. Though I initially tried to hide my scars and my depression from my family, this quickly proved too difficult. By the end of summer, I confided in my mother about what I was going through, and within the following weeks my pain worsened until I again threatened suicide. By October, I could no longer handle being in class and my attendance began to slip. Within a few weeks, I returned to Four Winds, the hospital where I had first been brought as a scared seven-year-old. It was during this stay that I met an out transgender person for the very first time, a connection which would have a profound impact on me as I continued to explore my identity. I confided in him that I thought I “might” be trans, but left it at that. I was still not ready to face my truth, even though denying it had become unbearable.

October 1, 2012 (age 17) – I look reasonably happy here, no? Less than a month later, I was admitted to Four Winds for self-harm and suicidal ideation. These were some of the darkest months of my life.

————

After leaving the hospital, I tried to return to class and catch up on my schoolwork, but my complete lack of motivation and energy made this feel impossible. Before winter break, I had a meeting with my mother, guidance counselor, principal, and case manager (I was assigned a case manager when I reentered public school in fifth grade) during which the principal asserted that I was “poisoning the school with my depression” (her ACTUAL FUCKING WORDS) and essentially threatened that I would not be welcome back at school unless I quickly got my act together. I tried going back following winter break, but after missing two of the first three days, my case manager called my mother to let her know that they would need to find a new school placement that had the resources to more adequately support my mental health. I was distraught — I had loved my time in this school, and though I had been struggling for the past few months, I had always assumed I would graduate with my class. My mental health plummeted further, and I returned to Four Winds the following week.

During this stay in the hospital, my family searched for a therapeutic day school where I could finish junior and senior years. In February, I started attending Sage Day in Rochelle Park, NJ, but after a few months, my mental state showed little sign of improvement. Unbeknownst to me, my family had decided to get in touch with an educational consultant — a fancy, vague title for someone whose job it is to find longer-term therapeutic treatment centers for struggling teens. She decided I would be a good candidate to attend Second Nature Entrada wilderness therapy, and later found Carlbrook School for me as well. Though I initially protested the idea of spending three months to two years away from home, I eventually realized that the pain of continuing to live with my depression was far worse than anything I could experience in therapy. Though my experience at Carlbrook was less than ideal, my stay in treatment allowed me to develop the strength and insight that I needed to eventually come out as transgender and pursue my truth, which ultimately led me to happiness.

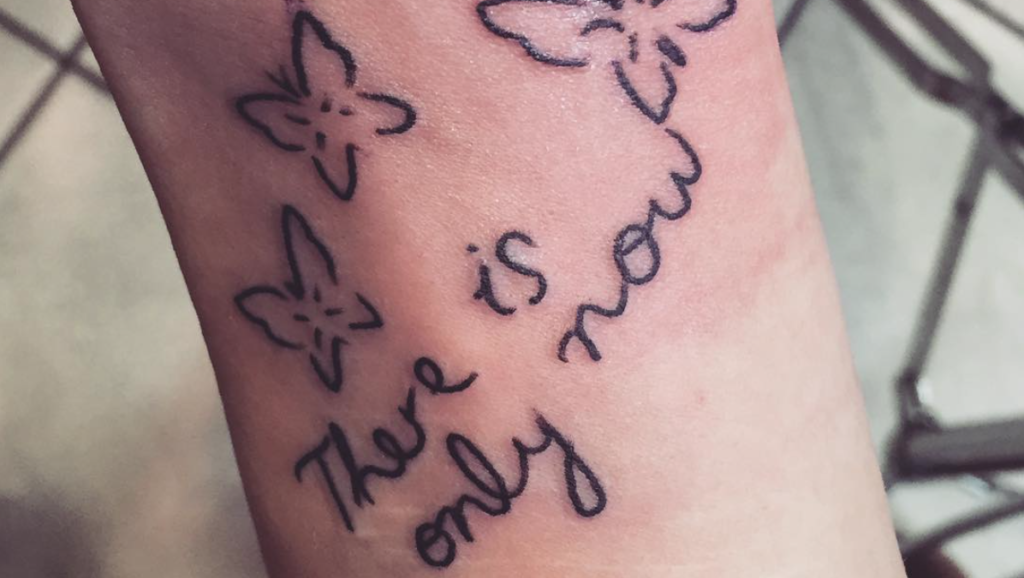

I got this tattoo in December 2015 to celebrate being two years self-harm free. It’s in my sister’s handwriting, and butterflies represent my mom, dad, and sister to remind me that even on my darkest days, there are people in this world who love me.

————–

In 2017, one study found that 14 percent of teenagers (17 percent of teenage girls and 10 percent of teenage boys) had attempted suicide. Among transgender students, these numbers are substantially higher, with this same report suggesting that over half of transgender teenage boys and just under a third of transgender teenage girls had made attempts. There are several factors contributing to this enormous disparity. Transgender teens face alarming rates of family rejection, bullying and harassment, and feeling unsafe simply for being who they are. A recent report by The Trevor Project found that 58% of trans and non-binary students have been discouraged from using a bathroom that aligns with their gender identity, which further stigmatizes transgender youth. National school climate has seen a recent uptick in hostility toward transgender youth, exacerbated by the Trump administration’s numerous attacks on the transgender community, such as rescinding Obama-era Title XII discrimination protections for transgender youth in schools and providing national platforms to anti-transgender speakers.

The way schools and communities treat transgender youth directly shapes our self-concept. When transgender youth are taught that there is nothing wrong with being transgender, given access to facilities that align with their gender identity, provided with positive transgender role models, encouraged to explore their gender identity, and given the proper resources and support from their community, school, and family to transition, they are able to thrive. Though this level of support for transgender youth has become slightly more common in recent years, especially along the west coast and in the northeast, there are still huge pockets of our country where support for trans youth is practically unheard of. In Gloucester County, VA, Gavin Grimm had to employ the support of the ACLU after he was refused access to bathrooms that aligned with his gender identity. The parents of an eight-year-old transgender girl in Grapevine, TX had to pull her out of school after her district failed to respond to bullying and refused her access to the girls’ bathroom. A transgender teen in Minnesota posted a video of school staff opening the bathroom stall she was using in order to deny her access to that facility. Transgender adolescents are frequently kicked out of their homes, harassed and bullied in school, given little to no support by their school administrations, denied access to trans-affirming medical care and mental healthcare, made victims of physical or sexual violence on the basis of their gender identity, and so much more.

When I entered the early stages of gender exploration, nobody I knew so much as used the word transgender, nor did they discuss queer issues. As far as I knew at the time, I was not just the only trans person, but the only queer person in my grade. My high school did not offer any guidelines or rules that explicitly protected transgender students from discrimination, nor did I ever hear thoughtful discussions among staff about how the school would accommodate transgender students. Between the three high schools I attended, I don’t remember a single time that a staff or another student referred to transgender people without me first introducing the topic, and even when I did introduce this topic, never once did we discuss trans people in a positive light. In my first high school, lack of trans representation made me too afraid to come out — by my third high school, I did come out, but was quickly outed to my family by my therapist and invalidated by a majority of the staff. All of this shaped my self-concept as a trans person — in not providing transgender role models, I came to believe that I was the only one. In not establishing specific protections for trans students, I came to believe that I would not be protected from discrimination if I came out. In invalidating my transness and refusing to speak to me about it, I was taught to be ashamed of my identity and made to doubt myself.

With all this considered, it is no wonder that transgender youth consider suicide at a rate so drastically higher than the general population — they are ostracized, ridiculed, discriminated against, harassed, and invalidated at a rate exponentially higher than other teens. It is not because we are transgender that we think about ending our lives, it is because of how society treats us simply for daring to exist. Yet, in a powerful testament to the strength and resilience of our community, we still exist. We persist. And in supportive environments, we thrive. It may not always be easy, but we continue to fight for the right to be our authentic selves in spite of often overwhelming mistreatment and abuse.

I began to transition about eight months after graduating Carlbrook. Although the first year was an incredibly stressful and scary time, working to align my external presentation with my inner sense of self finally set me free from a prison of masculinity that had brought me years of pain, dysphoria, and self-doubt. With the discovery of this new freedom, much of my depression and anxiety simply faded away, and it has now been over six years since the last time I self-harmed or threatened suicide. Cornell University’s What We Know project echoes this experience by outlining the astoundingly positive effects of gender transition on a trans person’s well-being.

While I was fortunate enough to find a supportive environment after high school and pretty quickly gain the support of my family along with access to trans-affirming therapeutic and medical care, this is sadly not the reality for a huge number of trans people. Sadly, lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts for transgender people remains at about 41% as they enter adulthood compared to 4.6% among the general population. The sad reality for transgender people is that harassment does not simply end as they graduate school. According to a 2014 report by Williams Institute, 50-59% of transgender people experienced discrimination or harassment at work, 60% were refused service by a healthcare provider, and 65% experienced physical or sexual violence. These, among other factors, contribute to the consistently high prevalence of suicide among transgender adults.

I implore each of you to do me a favor — show up physically and emotionally for your loved ones in need. Show the transgender people in your life, especially the transgender youth, that they are loved, supported, accepted, and cared for, even when the world tries to beat them down and force them to hide. Provide them with access to transgender role models, transgender support groups, trans-affirming therapeutic and medical treatment, and resources to learn about being trans. Love them unconditionally and check in on them when they are struggling. Show them that you care. You may not singlehandedly have the power to dismantle cishetero-patriarchal systems that encourage and reward systematic discrimination against transgender people, but you can certainly make a difference for the transgender people in your lives.

RESOURCES FOR TRANSGENDER PEOPLE AND PEOPLE WHO LOVE TRANSGENDER PEOPLE:

***Note: This is not an exhaustive list by any stretch. These are simply some resources that I’ve compiled over the years for supporting transgender people, teaching trans people about ourselves, teaching others about trans identities, and explaining to teachers and parents how best to support transgender youth.

PFLAG – varied resources – (My mom & I used to go to support groups here)

GLAAD – Resources for transgender people who are struggling and people who want to learn about trans identities with an emphasis on media coverage of trans people (I used to work here)

Trans Youth Equality Foundation – Specifically for youth, resources for learning about being transgender!

Transgender Law Center – legal resources – (My roommate works here)

GLSEN – Supporting Trans and GNC Youth (My former supervisor works here)

Schools in Transition: A Guide for Supporting Transgender Students in K-12 Schools – NEA (National Educational Association) in collaboration with NCLR, Gender Spectrum, HRC, and the ACLU

Trevor Project – Resources for trans youth to learn about trans identities, as well as TREVOR LIFELINE, TREVORCHAT, and TREVORTEXT, which are effective crisis intervention and suicide prevention resources for transgender youth

Trans Lifeline – Trans-specific suicide hotline for all ages. Call 877-565-8860 for support. *Note: If you look up this org, you may read some bad press detailing the arrest of two of their original founders for embezzling $350K from the org. The organization is in new hands, and I feel more confident in regards to its trajectory. Read the new founders’ comments here.

Trans-competent services in NYC:

Apicha Community Health Center – Offers trans and HIV/AIDS-competent medical care and community health education in Lower Manhattan. Has its own pharmacy. Call toll-free at 866-274-2429.

Callen-Lorde Community Health Center – Offers trans and HIV/AIDS-competent medical care, support groups, an adolescent-specific health program called HOTT, and dental services. They have two locations: one in Chelsea, Manhattan (212-271-7200) and one in the Bronx (718-215-1800). I’ve been to both and personally had really great experiences. Chelsea location has its own pharmacy. Additionally, they will keep seeing you even if you can’t pay your medical bills because they are more interested in helping people than making money (last year, they had $4M in un-repaid debt).

The LGBT Center – Offers a variety of services and support groups for LGBTQ+ people, as well as adolescent-specific programming. Located on 13th st. between 7th and 8th avenues. I interned here for a bit and have several friends who work here, and I really admire how much thought and time goes into creating their programming. The Center was founded in the 1980s, so they have a long history of supporting the community.

Ali Forney Center – Services for homeless LGBTQ+ youth.

PCYP – Legal services for LGBTQ+/homeless youth. Call toll-free at 877-542-8529 or e-mail pcyp@urbanjustice.org.

Pingback: The Most Powerful Tool in our Queer Arsenal – Trans and Caffeinated

Pingback: The Most Powerful Tool in our Queer Arsenal – Trans and Caffeinated

Pingback: The Number 1 Most Powerful Tool In Our Transgender Arsenal • Trans & Caffeinated