Since having my first consultation for bottom surgery (in my case, for vaginoplasty) two weeks ago, it’s been fascinating to hear all the ways people have reacted when I tell them about it.

Folks who don’t know me super well are shocked to hear that I haven’t already had it – in fact, I’m pretty sure a few of my coworkers are under the impression that in order to identify as transgender, you have to be post-op. Maybe they think that the word itself implies an operation. Or maybe, for them, it is unfathomable that a person who they see so plainly as female could possibly have a penis. None of this logic make much sense to me, but then again, I have likely had much more exposure to trans people than they have. It’s quite possible that many of them have never met an out trans person until me, so their knowledge of trans identities is understandably limited. This became clear to me recently after one coworker, Jessie, asked me if I was ever planning to get pregnant. With a little more mockery in my voice that I really intended, I retorted, “Jessie, I’m trans,” to which she questioned, “SO?!” which revealed to me two things: how little people have been taught about how trans bodies work, and how many people probably assumed that I’ve had a vagina this whole time. To be clear, at least with current technology, there is no way that I will ever be able to bear children, both because I do not and will not have a uterus, and because my vagina will be nowhere near elastic enough to endure childbirth (though, is anybody’s vagina REALLY elastic enough for childbirth?)

Many friends who are allies – people who are not transgender, but support and fight alongside the trans community – hugged me about as tight as I’ve been hugged in my life and offered variations of “I am SO happy for you!” and “This must be a dream come true.” In some ways, it is — but I’ve made this decision after years of being unsure about whether or not I wanted to have bottom surgery. To many of my friends, this acknowledgement of uncertainty is surprising.

Bottom surgery is not for every trans person.

I want to make one thing super clear: Bottom surgery is not a part of every transgender person’s journey. Because trans people are disproportionately affected by challenges like poverty, homelessness, familial rejection, hiring discrimination, and healthcare discrimination, many transgender people simply do not have access to bottom surgery. Not only is bottom surgery ridiculously expensive – you’re looking at between $20-30K without insurance – but there are a ton of requirements, like three third-party referral letters, someone to take care of you post-op, a diagnosis of gender dysphoria, etc. – than many trans people simply cannot meet.

Beyond lack of access, many trans people do not want bottom surgery, which is the idea that I really want to focus on today, mostly because this concept has proven so difficult to fathom by many well-meaning cisgender people (people who identify with the gender they were assigned at birth), and even some of the trans people in my life. Some trans people don’t want bottom surgery. “What?!” echoes a chorus of cis folx. “Then how can they ever feel like a ‘complete’ man or woman?” This concept, I believe, is the root of their misunderstanding – that within society, there exists an Absolute Maleness and an Absolute Femaleness that are naturally the goal for all trans people. Beyond that, there’s the assumption that those who are Absolutely Female must want to have a vagina and do not feel whole without one, and that those who are Absolutely Male must feel the same about having a penis. For trans folks like myself, these assumptions are taken one step further to suggest that I, a trans woman, must want to have a vagina so badly that I am unconflicted and enthusiastic to undergo a painful 5+ hour surgery, 1 week in a hospital bed, 6 weeks out of work, 3 months with limited physical functioning, and a lifetime of vaginal dilation just to have that brand new vagina that does most but not all of the things that a cis person’s does. And through the lens of the ciscentric (that which revolves around cisgender people) sex education that I am confident most if not all of us received, I’d be surprised if many of you didn’t think like this, unless you at some point were challenged to critically analyze and actively dismantle the way you were taught to think about gender. If you haven’t been — well, then, you’ve come to the right place!

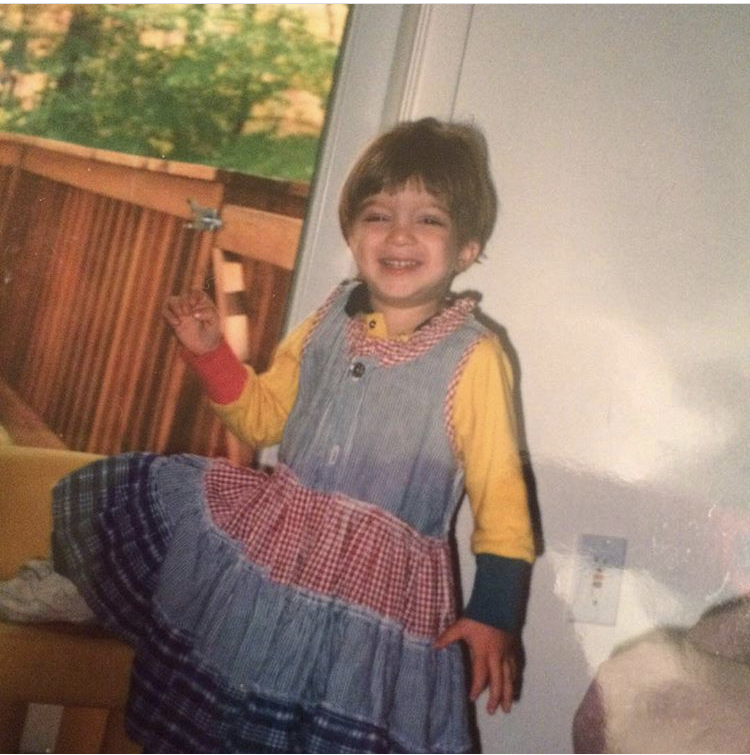

In many ways, my childhood was a pretty stereotypically transgender childhood. From the time I was around four, I thought about what it would be like to have a vagina. When I was a kid, though, I never really stopped to think that this made me different from other kids my age. Sometimes, when I was alone in the bathroom, I’d tuck my penis between my legs, and look down at the smooth appearance of my crotch below. If I positioned it just right, I was sometimes even able to make it look (from my vertical perspective, and based on my limited knowledge of the appearance of vaginas) like there was an indentation in the underside of my pelvis, one that I could imagine for one moment of respite was my vagina. You have to understand – to a little kid, especially to one assigned male at birth, understanding of genitals is pretty much limited to the external appearance of these organs. So at that time, that small indentation was enough to give me joy, if just for a fleeting moment.

As I grew up, I began to understand the implications our perceived anatomy has on the ways in which we are allowed to move throughout the world. Though I had a rough self-concept of being female from my earliest memories, I was unable to vocalize it in a world that had to that point failed to teach me tools nor words to discuss gender expansiveness. So by the time I was eight, I frequently became overwhelmingly upset to find that that I was excluded from activities with my female friends purely because I “was a boy.” I understand that they had no reason to see me as anything else, regardless of how I saw myself – but to my young mind, it pained and confused me that they saw me as so drastically different from themselves that they no longer wanted me around.

At this point, the vagina began to attain a symbolic status in my life. For young Arielle, vaginas became a symbol of everything I wanted for myself but feared I may never have — because in our society, having a vagina grants you permission and access to an entire world of likes, dislikes, emotions, social groups, and activities from which I felt restricted. A vagina was a ticket to princess dress-up parties and tea parties, dresses and skirts, the colors pink and purple, the freedom to express sadness without shame, to feel joy without limits. It was also a ticket to what would become my biggest battleground as teenager: The Slumber Party. For me, nothing made me feel more lonely and isolated than my exclusion from sleepovers as I hit adolescence. Between their parents’ discomfort, and though most of them wouldn’t admit it, likely the discomfort of several of my friends at having a “boy” at their sleepovers, I spent what felt like a million weekend nights sitting at home in my bed, crushed by the knowledge that yet again, all of my friends were having a sleepover that I wasn’t invited to. If only I had a vagina, I thought. By middle school, in reaction to years of pressure and taunts from my peers, I gave into the long-circulating rumor that I was a gay man, and I temporarily claimed this identity. For me, this was a decent compromise to coming out as transgender, which was something I had not yet fully processed nor accepted myself to be. At least as a gay man, I was invited to some of these gatherings. But being gay could not really make me feel like one of the girls — that was a club that seemed exclusively limited to vagina-havers.

As I reached the end of high school and continued to wrestle with my then undeniable and overwhelming transness, I decided I had to speak my truth. On October 10th, 2013 (National Coming Out Day of that year), I got up in front of the staff and students of my Virginia boarding school and boldly proclaimed two things, 1) I am transgender, 2) I am going to have bottom surgery by the time I graduate high school. I know this second assertion was naive, but in the whirlwind of panic and excitement that accompanied my early days of thoughtful gender exploration, I had never quite thought to stop and research what the process of medical transition would actually entail. In that moment, I was so caught up in the excitement and the thought that I could one day, finally, have the one thing that I had so long dreamed of having that I frankly got carried away. And at that time, bottom surgery seemed like the solution to all of my problems. I was devastated when school counselors sat me down and essentially forbade me from transitioning while enrolled there, simultaneously writing off my coming out as a desperate grab for attention. Though this was completely uncalled for, and their subsequent refusal to engage in any meaningful discussion about my transness while I was enrolled was unjustified, unprofessional, and outright cruel, their response had a very important silver lining: it forced me, for the very first time, to take a step back and to look at my gender journey – past, present, and future – and to gain perspective on what womanhood truly meant to me. Though painfully long and arduous, this journey led me to the profound realization that womanhood is about so much more than anatomy. I had become so distracted by our ciscentric society’s unwavering and dehumanizing reduction of womanhood to having a fully functional vagina, uterus, ovaries, etc., and by my own associations with this particular anatomy, that I had never quite stopped to process what womanhood meant to me.

Womanhood is a complex concept and it is important to understand that it is socially constructed, meaning that its definition is shaped and transformed over time by the social rules and expectations that are set forth for women within a given society. Though traditional, conservative society asserts that womanhood is a consequence of having been born with two X chromosomes (and often even dumbs this down further to having been born with a vagina), the sheer existence of transgender people proves this to be untrue.

For a long time, I thought that I needed a vagina to be taken seriously as a woman. And truthfully, it is often incredibly challenging to be a woman who does not have a vagina. More times than I can count, I’ve been rejected by a potential romantic partner simply because I have a penis. For the past year, I’ve been experiencing immense pain during sex as a result of tucking – a technique that many transfeminine people use to create a ‘feminine’ contour and avoid having an obvious ‘bulge’ in the front of their pants. Most techniques accomplish this by holding the penis underneath the individual, facing their buttocks, and the testicles inside their inguinal canal. Even after four years of tucking, I often get anxious in tight-fitting clothing out of sheer terror that somebody will somehow be able to tell that I have a penis while I’m walking down the street and that I could be attacked, and I continue to tuck tightly despite the pain that it causes me. The beach used to be my happy place, but I only just went to a beach for the first time in five years because the thought of wearing a bathing suit in public had long crippled me with anxiety. Even now, I mostly only feel comfortable at Riis beach, which is a queer and trans beach in Queens. I am constantly bombarded with transphobic rhetoric by any number of public speakers, congresspeople, senators, Youtubers, peers, presidents, and strangers on the subway who assert that anybody who has a penis is a man, and that trans women are nothing more than “men pretending to be women.” My right to use public restrooms has been debated in at least 16 state legislatures, which has given a platform and a voice to fear-mongering transphobes who, with no rational basis, insist that allowing transgender women to use the women’s bathroom will lead to more assaults on cisgender women in restrooms — news flash, there have been zero documented incidents of trans people attacking cis people in bathrooms, while the incidence of cisgender people attacking transgender people for simply existing in public spaces is extremely high.

In spite of all of this bigotry, transgender women like myself continue to thrive. For a long time, I didn’t understand how — but as I’ve grown into my womanhood over the past four years, the explanation has become. The very existence of transgender women challenges conventional notions of womanhood. In defining womanhood on our own terms, we challenge ourselves and the rest of society to rethink what we have all been taught about gender – that gender and anatomy are intricately woven together and cannot be separated. We’ve been taught that women have vaginas and men have penises – and based on a limited understanding of transgender people, many well-meaning cis people has been taught that a transgender woman’s transition is only “complete” once has recovered from vaginoplasty. This is a load of bullshit, and my womanhood is no less valid now than after my surgery — furthermore, my womanhood would be no less valid had I decided that I was never going to have surgery. For me the decision to schedule bottom surgery was not rooted in a realization that I could never be happy or fulfilled or feel complete or valid or have good sex without having bottom surgery. It was not the result of crippling bottom dysphoria (emotional or psychological discomfort with the appearance of one’s genitals)- to be honest, my bottom dysphoria has been pretty mild this past year. Sure, I want to have a vagina. I’ve wanted one for years and for a long time, the question I asked myself when considering bottom surgery was whether my bottom dysphoria was emotionally draining enough that I felt it was worth undergoing major surgery. This was a question I never quite felt I could answer. Ultimately, my decision was not based on the severity of my bottom dysphoria, but rather on a few simple but crucially important realizations: First, that life will simply be easier for me if I have a vagina – easier within the context of a society that, unfortunately, places greater validity in my womanhood and treats me far more kindly if I have a vagina. The risk of being attacked or killed by a sexual partner when they realize I’m transgender goes down considerably. The risk of being romantically rejected for this reason plummets as well. The risk of being clocked (having somebody read me as trans without my coming out) because I’m wearing a bikini or wearing tight pants goes away. Truthfully, many of the challenges I’ve faced as a transgender woman have been rooted in my having a penis instead of a vagina. The second realization was that although I can be happy without having a vagina, I could be happier with one – that is, I could feel more fulfilled, feel more gender euphoria, have a better sex life than I could without having surgery.

My decision about surgery could very easily have gone the other way, especially within a far more progressive society than our current one. I am assured now that this is the right choice for me, but I know that is not true for everybody – so if you get one thing out of reading this post, let it be this: The validity of a trans person’s identity is not rooted in wanting or needing or actually having bottom surgery. The validity of a transgender person’s identity is rooted solely in their telling you that they are transgender.

That being said, after 24 years of waiting and deliberating, I am hella fucking pumped for my new vagina. Thanks for the congrats, y’all.

This was very interesting for me to read and I related to a lot of it (the feelings more than the specifics, seeing as I’m transmasc). Thank you so much for sharing and educating and congrats on your new vagina!

Pingback: Trigger Warning: Suicide – Trans and Caffeinated

Pingback: Transgender Healthcare is NOT Cosmetic. Employers, it's time to step up your game. • Trans & Caffeinated

Pingback: I Always Knew She Was My Sister: On Loving My Transgender Sibling • Trans & Caffeinated

Pingback: “You Don’t Look Transgender!” and Other Micro-Aggressions to Avoid • Trans & Caffeinated

Pingback: Transgender Healthcare Is Not Cosmetic. Employers, It's Time to Offer Comprehensive Care. • Trans & Caffeinated

Pingback: 4 Months to Bottom Surgery: On gaslighting, Agonizing Self-Doubt, & An Eye-Opening Therapy Session • Trans & Caffeinated

Pingback: A Bottom Surgery Chronicle: ALL My Dysphoric + euphoric Musings ON Vaginoplasty, 2019-PresenT • Trans & Caffeinated