Trigger warning: This post mentions sexual objectification of minors, anti-trans violence, and genitals.

1. Simply by being visible, I challenge conventional notions of sex and gender

As I’m writing this, I’m sitting in Prospect Park with my friend Jeff talking about how gender roles as we now know them came to be. The truth is, much of what we assume to be true about men and women is the result of colonial gender ideals, which is why gender roles differ so drastically in the eastern and western worlds. A primary assumption of colonial gender roles is that one’s behavior is directly determined by one’s genetics — the idea of biological determinism. More specifically, many people have been led to believe that a baby who is assigned male will naturally develop an interest in certain activities, display certain attributes, be more inclined towards certain patterns of emotion, etc., and that a baby who is assigned female will differ drastically in these characteristics. The existence of transgender people proves this assumption untrue.

When I was born, the doctors took a quick glance between my legs and proudly proclaimed, “It’s a boy!” From that moment forward, my parents and others around me developed expectations for how I would behave, what my interests would be, and who I would love. As I grew up, my dad expected me to be interested in sports, and seemed disappointed when I wasn’t. I was extremely emotional “for a boy,” and other kids teased me for this in school.

I felt more comfortable and more myself around girls because I had far greater connections and mutual interests with them than with the boys in my class. I enjoyed playing dress-up, singing and dancing, and watching shows and movies created for girls. The interests I developed on my own differed significantly from those of boys my age, and from the time I was little, some of my classmates found it amusing to mock me for “being a girl.” In reflecting on how frequently I heard this comment as a kid, I’ve realized a few things: First, because children primarily learn how to interpret and respond to the world by observing adult around them, the fact that they knew to label my behavior as “girly” suggests that adults in their lives had already made a clear distinction between what boys and girls should like. Second, it showed that these adults had shown them it was acceptable to mock people who did not fall neatly into these gender roles.

Within the past few years, several of my friends have gotten married and/or started to have children of their own, and I have been extremely vocal in challenging their gendered assumptions. Whenever people tell me, “I’m having a boy!” I ask, “How are you so sure?” because the fact of the matter is that while you may be able to tell what parts your baby will have from a sonogram, there is no way to know how that baby will identify in terms of gender. There is no way to predict their interests or anything about their personalities, but that has rarely stopped mothers from talking about how excited they are to have a baby girl who they can put in pretty dresses and one day talk to about liking boys. It hasn’t stopped fathers from buying their male-assigned baby a tiny baseball cap and foam baseball bat before he is even born, or from fantasizing about the first time they’ll go to a game together. These assumptions can cause a children, especially those who are transgender, immense psychological harm — by forcing kids into gender boxes from an early age, we inhibit their ability to authentically explore the world around them because we tell them, based on their gender, what they should or shouldn’t enjoy, be, and feel.

My hope for cisgender people is this: as you learn more about transgender lives, you come to understand that a quick glance between the legs tells you nothing about your baby beyond what genitals they have. In being visible and speaking candidly about the challenging realities of growing up transgender, I hope to discourage those around me from parenting their children through a gendered lens. As myself and other trans people continue to be visible and cis people continue to observe, I hope that we can to dismantle gendered expectations and the faulty assumption that one’s gender is a direct result of their sex assignment.

2) I’m able to speak to the power that authenticity has to improve our lives

Like many queer and transgender folks, I have battled ongoing mental illness for much of my life and have cycled through a whole host of diagnoses aimed at explaining my unhealthy patterns of behavior. Throughout my youth and early adolescence, I was either formally or informally diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder, depression, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), and Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). When I was diagnosed with BPD at age 18, a psychologist told my family that I may never fully be able to escape my unhealthy behavioral patterns, and that my only hope of leading a healthy, happy, fulfilling life was to spend time in long-term, intensive, inpatient therapeutic treatment. As a result, my parents convinced me to go to a three month wilderness therapy program called Second Nature Entrada (now Evoke Therapy Programs at Entrada), followed by a 16 months stay at a therapeutic boarding school. While I definitely gained a lot from my time in these programs, there was always something standing between me and a happy life, because the version of myself who I was at the time was largely inauthentic. People picked up on this, too, and frequently commented that I seemed “fake” and “attention-seeking,” when the reality was that I was struggling and cracking under the pressure and pain of living as someone I was not. This put on a strain on both my relationship with myself and my relationships with others. It made navigating the world incredibly difficult, because I knew that the person people saw when they looked at me was not who I was inside. Even as I shifted from living a lie to living a half-truth by starting to speak more openly about my trans identity towards the end of of high school, my crippling fear of diving headfirst into authenticity held me back from achieving my full potential.

After graduating boarding school, I began searching for a job that would fill my time during the eighth month gap before starting college. I intentionally searched for trans-friendly employers because I was actively inching toward the start of my social transition and knew that I could not mentally handle being in another environment that was unsupportive or invalidating of my gender identity. The employer who came up most consistently was Starbucks, so I immediately applied to a few stores in my area. Within a week and a half, I began training as a barista — and within five months, I began to test the waters of support by coming out to a few coworkers who I felt would stand by me throughout my transition.

On August 30th, 2015 — eight months after graduating Carlbrook, and seven months after beginning to work for Starbucks — I made the difficult decision to begin to live authentically. On that day, I stepped onto Ramapo College campus for my first day as a college student, and stepped into what felt like the first real day of my life.

As I continued to grow into my authentic self, I made a fascinating discovery — the more authentically I pursued my truth, the less I exhibited symptoms of BPD. The more comfortable and confident I felt in my skin, the less I felt the need to seek attention. The more honest I was with others about my identity, the less volatile my relationships became. The more tools I found to identify and soothe the causes of my gender dysphoria, the less frequent and intense my mood swings. The greater my commitment to living as my authentic self, the more mentally healthy I began to feel. I developed healthy tools for managing my depression and anxiety, and became increasingly vocal about my experiences as a transgender woman.

This is the power of authenticity — because to be authentic is to be the most you that you can possibly be, which means that the maladaptive coping mechanisms that so many of us develop to hide our insecurities from the world simply melt away. For me, being authentic meant coming out as transgender, but so many of us have some truth or reality with which we grapple to come to terms throughout our lives but causes us a great deal of mental anguish. I firmly believe that the more empowered we are to accept our truths, the greater the happiness we are able to achieve.

I want to make note of the fact that being able to live my truth as a transgender woman is a privilege, and one that I do not take lightly. So many transgender people are unable or unsafe to come out for fear of being kicked out of their homes, rejected socially, attacked, ridiculed, etc. Though my family struggled with my identity initially, I was never at risk of losing financial support or a place to live. My friends and my incredible sister immediately responded to my truth with immense, unconditional and overwhelming love and support, followed shortly after by my mother and then my father. I’ve gained an incredible community of other transgender people who have supported me and stood by my side throughout my journey. I owe my ability to openly and unapologetically live this truth to each of them.

3) I get TWO birthdays!

Within the transgender community, it is pretty common to claim either the day we came out or the day we began to live our truths as a second birthday — for many of us, this day feels like the real start to our lives, because it i often the first day that we are able to navigate the world as our true selves.

I was born on March 5th, 1995 — but on August 30th, 2015, I entered my Ramapo College dorm, put on makeup, walked down to the Freshman quad, and began consistently introducing myself as Arielle for the very first time in my life. Out of habit, I still generally celebrate my birthday on March 5th, but I will always make note of August 30th as the day that I stepped into my new life as a woman — the day that Arielle was born.

4) The way I experience sexual pleasure has changed considerably, which means I have a broader understanding of how partners of different genders experience sexual pleasure

Because of an absurd and extremely counterproductive cultural taboo around sex, most people are completely unaware of the differences between the way that people with high amounts of estrogen and people with high amounts of testosterone experience sexual pleasure. To be honest, I had no idea how drastic these differences were until a therapy session I had the week before beginning HRT (Hormone replacement therapy), which for me involves a combination of injectable estrogen and a testosterone blocker called Spironolactone, which is also commonly prescribed to people with PCOS.

Even though I’ve been out as transgender for four years, I only started HRT two years ago — therefore, up until that point, my orgasms closely resembled what many cisgender men experience, because my hormone levels closely matched theirs. For people with these levels, the orgasm is rather short — typically under 30 seconds — and is most often experienced as a singular, intense sensation largely localized to the penis. Before beginning HRT, this was my experience of orgasm, too.

After being on hormones for two years, my orgasms have changed drastically and now more closely resemble those described by cisgender women. During my orgasms, sensation in my penis is far less intense, and instead spreads throughout my entire body. My hands and feet pulse, my body feels warm and extremely sensitive, and I breathe much more heavily.

Although many folks do understand on some level that people of different genders experience orgasms differently, most people do not understand exactly why or how. Being transgender and on HRT has given me a unique perspective on these experiences that has improved my sex life immensely, and I feel incredibly blessed to have this understanding.

5) I get to experience bodily changes when I’m old enough to understand the way the world will respond to them

I want to make clear that I only know secondhand what it’s like to be an adolescent who is read as female. Much of my understanding about these experiences is based on a combination of my own observations, stories shared with me by others, magazine articles, and academic journals. However, I do know what it’s like to be a teenage girl who is not read as female, and I know what it’s like to be an adult who is read as female, which gives me a unique perspective on this subject.

—

Many young people who were assigned female at birth (AFAB) begin to develop breasts and become generally more curvy during puberty. Disturbingly, there is pretty rapid shift in the way people respond to these young folks as soon as these changes occur. Our society — and specifically men — sexualizes these young peoples’ bodies, and at ages 12-14, this experience often has a drastic and detrimental effect on their mental health. These experiences can be traumatic and terrifying, and nobody should ever have to endure this — but the sad reality is that many folks do, and it is next to impossible to protect or shield them from such sexualization.

As a transgender woman, though I endured my own puberty-related traumas of growing facial hair, my voice dropping slightly, and my shoulders broadening, I feel blessed that I avoided much of the trauma that my friends endured at the hands of society. I consider myself blessed that I did not at a young age have to endure the nonconsensual sexualization of my body by a society that treats young AFAB people as objects, at the very latest, from the moment they gain curves.

Instead, I grew breasts and got fat deposits in my hips around age 20, when I was old enough to understand the way the world would react to me as these changes occurred. When men stare at my breasts or comment on my body, I have the self-assurance and confidence to criticize their behavior. When I look at a magazine and see a woman my age with larger breasts or more pronounced curves than myself, while it is difficult not to compare myself to her, I at least rationally understand that the standard set by these images is unrealistic and unattainable. For many young girls, these words and images have a detrimental effect on their mental health as they come to understand their bodies and develop body confidence within a world that is constantly policing, criticizing, and sexualizing their bodies. Though I certainly had my own insecurities stemming from a desire to look a lot more like the beautiful, impossibly skinny yet simultaneously big-busted women on magazine covers, nobody criticized me for not looking like them. Because of that, my self-concept and self-confidence developed apart from these comments rather than being shaped by them.

6) Unless I’ve intentionally kept up with them, people from high school don’t recognize me

High school is a dark time for a lot of us. I don’t know about you, but I don’t generally enjoy having to relive my high school memories, and I definitely don’t enjoy running into people I didn’t like in high school. Unfortunately, these run-ins happen way too often whenever I’m back in my hometown. How many of us can say that we’ve never turned around in a supermarket to avoid an awkward, obligatory interaction with someone we knew from childhood or adolescence but never quite liked? How many of you has ever seen your childhood bully at a coffee shop while you’re, say, on a first date and had to simultaneously navigate avoiding awkward eye contact with them and the awkwardness of a first date?

Fortunately for me, people I haven’t seen since high school rarely recognize me, so the ball is pretty much entirely in my court! Unless I’m friends with someone on social media, chances are they have absolutely no idea who I am when they see me, which means noawkward eye contact, noobligatory “hellos” or “how ya doings,” nomindless small-talk. Nope! I don’t have to deal with anyof that. And if that ain’t trans privilege, I don’t know what is.

7) I have a greater and more nuanced understanding of the way gender affects our everyday lives

Transitioning has given me a profoundly unique perspective about how the gender others perceive us as influences the ways in which we are able to move about the world. This allows me to speak from personal experience to the immense power that maleness affords people within our society.

Prior to my transition, I was typically read as a white, effeminate, gay man. Though being read as gay created certain obstacles, I navigated the world with the immense, incomparable privilege afforded to well-off white men in our society. I could walk down the street at night without fear of sexual harassment. I could dominate a conversation without being perceived as “too talkative.” When I became emotional, no one in the room would assume it was because I was hormonal. I could be assertive without being perceived as “bossy” or called a bitch. Until I transitioned, however, I was blissfully unaware of how drastically male privilege affected the ease with which I was able to navigate the world.

As I transitioned and began to be read as female with increasing frequency, I watched as I began to lose many of the privileges I had previously taken for granted. Instead of being commended for my strong leadership skills, I received criticism for being too “bossy.” Instead of being praised for how assertive I am, I was told I was being rude or “bitchy.” Nearly every time I leave my apartment, men catcall and harass me and call me a bitch when I don’t respond. I feel the need to carry pepper spray at all times out of fear that I’ll be assaulted on the street simply for existing while female.

Though I’m admittedly still afforded immense privilege from being a white, pretty, middle class woman with a roof over my head and a well-stocked fridge, transitioning cost me the innumerable freedoms that male privilege once afforded me. This is in no way to say that I regret transitioning, and I feel incredibly lucky to be consistently read as female, but I do resent the fact that being read as female means that society treats me with substantially lesser respect, compassion, and dignity.

8) I get to use my life experience to support and educate others

Over the past few years, one of the comments that I’ve heard most frequently is, “you’re the first transgender person that I’ve ever met.” While I don’t believe that is totally true in every case, I do believe that I am the first transgender person they’ve ever met who has been out as transgender to them. As trans people, and especially for transgender people who are not read as transgender, it is substantially easier, less emotionally taxing, and less terrifying to exist while transgender if you avoid outing yourself as transgender until it is absolutely necessary to share this information (for example, with a sexual partner). By a year into my transition, I was no longer read as transgender, which brought me to a fork in the road – On the first path, I would begin to live comfortably within my “passing” privilege, rarely acknowledging to others that I am transgender. On the second, I would push myself outside of my comfort zone and share openly about my trans identity, using my experiences to help educate and support those around me. I turned to the voices of transgender activists Laverne Cox and Janet Mock, both incredibly candid and articulate about their identities, and found myself consistently moved to tears by how seen and validated their words made me feel. Through listening to them speak, I decided to walk the second path. In doing so, I found such profound fulfillment in the impact I was able to have on those around me that I decided to continue sharing.

Today, most people who have spent more than five minutes in a room with me know that I am transgender — it’s even in my Instagram bio. In explicitly queer or queer-affirming spaces, I often lead with this information when introducing myself. I have spent the last few years growing increasingly confident and comfortable sharing the intimate details of my transition. As a result, those around me have become increasingly comfortable asking me questions about the transgender community or about my transition specifically. As I’ve continued to share information, I’ve watched the cisgender people in my life become increasingly supportive allies as they carry what they’ve learned from our conversations into other spaces.

I used to feel uncomfortable when people asked me about my surgical status or to see pictures of what I looked like before transitioning, but I’ve reclaimed power in these situations by sharing this information before people even have the chance to ask. I typically make note of the fact that while I am happy to share that information, it is inappropriate and invasive to ask transgender people such questions.

Because I am so open about my experiences, people frequently reach out to connect me with other transgender people they know, and many transgender people have felt comfortable coming out to me before coming out to their loved ones. These connections have given me a stronger sense of community along with the ability to support a growing number of transgender people who feel seen and validated by seeing another transgender person being out, proud, and unapologetically trans. I have have had the incredible honor of supporting these folks in the early, often timid days of their transitions and watching them grow into badass, confident, self-affirmed transgender people.

9) Everything I am is something that I fought for

Obviously, this isn’t a trans-specific phenomenon. Plenty of you have had to fight like hell to be your authentic selves in a world that fights tirelessly to force you into the cookie-cutter life that someone who looks like you is “supposed” to lead. Personally, I had to fight to be accepted and perceived as a woman in world that tried for so long to pigeonhole me into a prison of masculinity.

When I first came out at boarding school, my proclamation of womanhood was not exactly met with enthusiasm. As I mentioned in my last post, I was essentially forbidden from transitioning while I was still enrolled there. When I pleaded with our second headmaster that I be able to explore my gender, perhaps by wearing dresses or having the small amount of makeup that other girls at the school were allowed, I was told that this would make the other parents uncomfortable & that he was unwilling to risk that. At the time, admissions were in steady decline, and I suspect that the fear of transphobic parents deciding not to enroll their students after seeing a transgender student wearing a dress in the dining hall was enough to squelch any desire he may have had to support my transition.

Toward the end of my boarding school stay, I spent a lot of the one-on-one time I had with my parents trying to convince them that my gender identity was valid and that I needed a trans-affirming therapist to help me navigate transition. I tried to compel them to sympathize with my struggles and to understand that my therapist’s interpretation of the situation was blatantly inaccurate. However, the mental health professionals at my school told them that I was lying, and my parents wanted to believe them out of fear that my life would be more difficult if I were actually trans. Any time I tried to discuss my trans identity without my therapist present, my parents — especially my dad — were visibly uncomfortable. The catch-22 was that while they were uncomfortable discussing this without my therapist in the room, I was uncomfortable discussing it with him in the room after he had outed me to them and so poorly misconstrued my motivations for coming out.

After enduring overwhelmingly invalidating responses to my trans identity for the year and a half, I was terrified that people back in New Jersey may have similar responses if I decided to transition. I also feared that perhaps I wasn’t really transgender after all — that perhaps my therapist had been right all along and I really was just doing this for attention. A year and a half of navigating Carlbrook’s transphobia had caused me to doubt my identity, even though I had felt female for years prior.

After nearly five months of living in fear of coming out to my NJ friends, and another three months of being afraid to transition out of fear that my parents would respond negatively, I approached a turning point. In the months before college, I asked my roommates-to-be (one of whom was trans masculine & non-binary) how they would feel if I began to transition when we started school. Each of them offered beautiful words of love and support, and I spent the next few months working up the courage and confidence to do this.

On the first day of college, I started to transition. My gender journey began with a soft-launch — when I refer to the “start” of my transition, I refer to the moment that I started wearing makeup, introducing myself as Arielle, and insisting that people refer to me using she/her pronouns at all times. I did not medically transition for another two years. Still, this was enough to make my father — who had not yet worked through his own discomfort and insecurities around my transness — extremely uncomfortable. After meeting me as Arielle for the very first time, I received a phone call that would shape the course of the remainder of that first year.

One night, my dad called and told me that we “need to talk” — three words that hardly every lead anywhere happy. I immediately got a lump in my throat. I responded with a feeble, “Yes?” He proceeded to tell me that he had been extremely uncomfortable seeing me in makeup and insisted that people had been staring at me and judging us because of it. As the conversation became more heated, he compared my wearing makeup in public to him “walking around with [his] penis hanging out of [his] pants for everyone to see.” I can’t even remember everything that was said on this phone call, just that each comment was soul-crushingly painful. We did not speak a word to each other for six months (though it felt like years).

During that six month period, I exploded into my new life with equal parts terror and excitement. I became more skilled at applying makeup in ways that would feminize my features, I bought breast forms so that my chest would no longer appear flat when I was wearing clothing (which in turn calmed dysphoria related to my chest), I turned 21 and started going to clubs as my authentic self, I learned how to tuck in order to feminize the appearance of my crotch, and I learned how to advocate for my needs and the respect that I deserved. While I was heartbroken that my father did not want to know this exciting side of me, the space between us allowed me to freely explore my womanhood unhindered by his insecurities. Fortunately, he continued to support me financially during this time, which is a luxury that many transgender people simply do not have.

By March, he had seemingly worked through enough of his fears that he decided to reach out to me. For my 21st birthday, he offered an olive-branch — a birthday card with an image of a man and a little girl with the words “Happy Birthday, Daughter” in that beautiful Hallmark cursive scrawled across the top. Initially, I was apprehensive at best that he had actually accepted me. But when we finally met for dinner a few weeks later, he approached me with tears in his eyes. He looked at me, took a breath, and told me that I looked beautiful. I had never dared dream that he would say this.

From that point on, he unquestioningly supported and trusted every transitional step I needed to take, both financially and emotionally.

Shortly after that dinner, I started seeing a transgender therapist in hopes that we could work through trans-specific challenges together. Because most states require you to have a diagnosis of Gender Dysphoria in order to pursue any transition-related healthcare, finding a trans-affirming therapist was a crucial step in beginning my medical transition. About a year into working with her, I decided I wanted to begin HRT, and she referred me to Callen-Lorde Community Health Center in the Bronx. In August 2017, I finally started taking hormones. Over the past two years, I have been delighted as my breasts have grown larger, my hips and butt have gotten more curvy, my skin has gotten softer, and my cheekbones have begun to appear higher and more full.

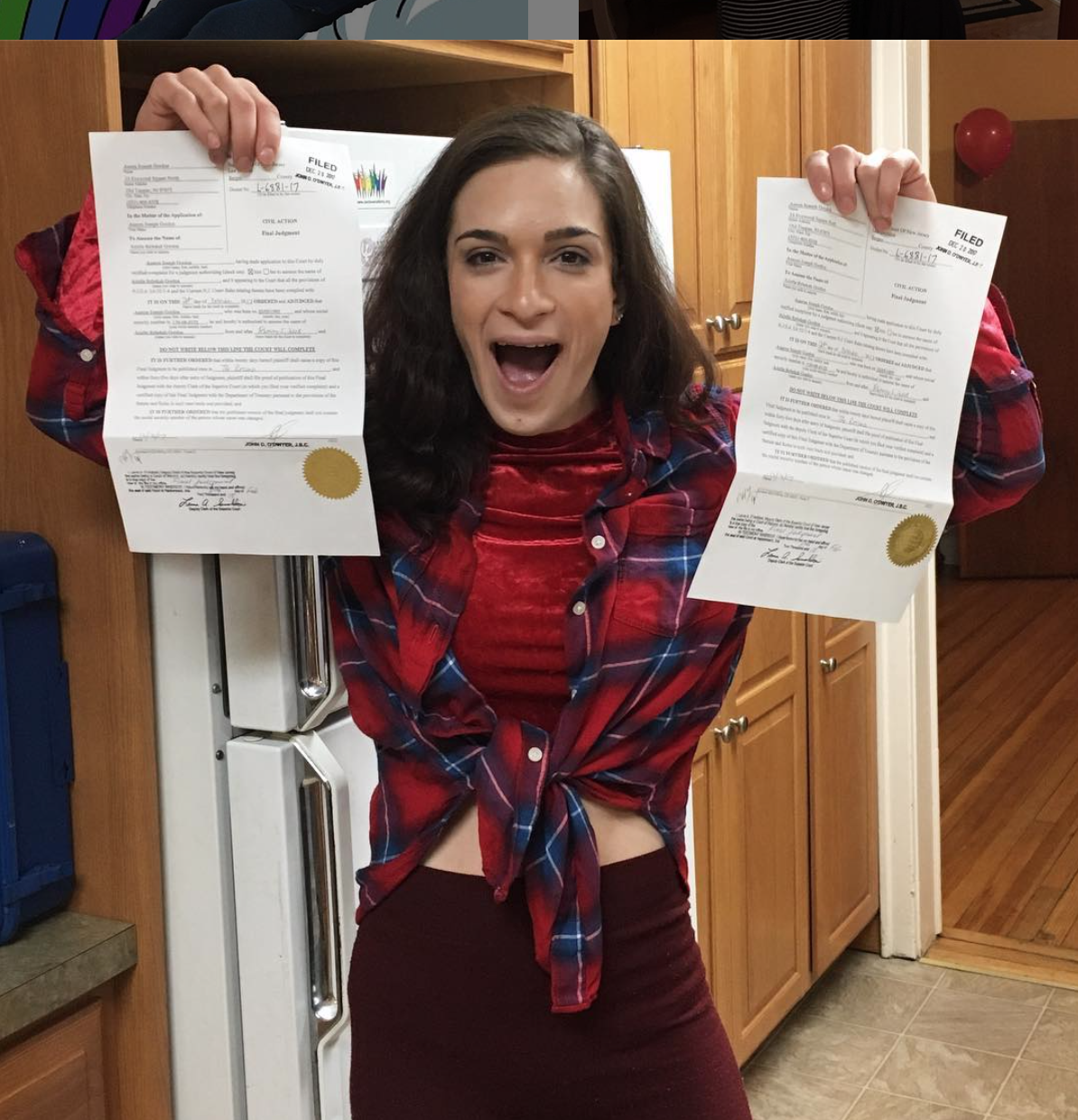

During this time, I also navigated the arduous eight-month process of obtaining a legal name and gender marker change, which involves immense amounts of legal gatekeeping and red tape. I crossed my t’s and dotted my i’s, and on February 5, 2017, a New Jersey judge signed a court order stating that following a mandatory 60-day waiting period, I would legally be known as Arielle Rebekah Gordon. By the end of April, my passport, driver’s license, and social security number all reflected my name and gender. I cannot describe the complete euphoria of seeing that little “F” on my license for the very first time.

Seven months ago, I made scheduled my first bottom surgery consultation (which y’all know all about from my last blog post!), and worked with three separate mental health and medical practitioners to obtain the three separate referral letters that I needed to have my insurance give the go-ahead for me to have bottom surgery.

Transitioning socially and/or medically is — technically speaking — a lot of fucking work. It is endless emotional labor, hundreds of hours of internet research, compelling everybody to accept you and respect you for who you are, booking doctors appointments, navigating pointless red tape in doctor’s offices and courtrooms, learning how to navigate womanhood in our society, learning how to apply makeup, learning how to tuck, tape, and gaff, learning that bras are a terrible, oppressive invention that force my breasts into a sweaty boob prison for at least twelve hours a day, and so much more.

(P.S. I just searched “Why were bras created?” and found that a woman in New York patented the first brassiere because she was tired of wearing corsets.)

Transgender people have to fight like hell, every single day, simply for the right to exist and to be who we are. I have fought so hard to get where I am today — every transgender person has — which makes being myself feel that much more rewarding and powerful. And if this doesn’t make transgender people just about the most badass people in the world, I don’t know what does.

10) Have you seen how fucking fabulous I am?

Here’s a transformation pic to prove that I’ve been hot in two genders.

I really do enjoy being transgendered. I always thought I was just a crossdresser. But now I know that every spare moment I change into a dress and make up